Tree of Souls

The Mythology of Judaism

Review

-

By

Roger G. Baker,

Howard Schwartz. Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism.

New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Readers who hear “myth” and think “untrue” will not appreciate the encyclopedic collection of nearly seven hundred myths of Judaism in Tree of Souls. Readers who understand that myth goes beyond the Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of “traditional stories” and understand that myths are truth beyond historicity, will read Schwartz as someone who craftily merges Bible, Midrash, Talmud, and works kabbalistic, Hasidic, and rabbinic to discover the cultural and spiritual DNA of modern Jewish, and by interpolation, Christian belief and practice.

Those who view myth as an explanation of why we believe will enjoy Tree of Souls. Schwartz is very clear on his definition of myth: “Myth refers to a people’s sacred stories about origins, deities, ancestors, and heroes. Within a culture, myths serve as the divine charter, and myth and ritual are inextricably bound” (xliv). According to Schwartz, there are ten divine stories in Judaism and each includes submyths. His ten-myth paradigm organizes the book and makes it accessible to both scholar and student.

Tree of Souls is critically acclaimed, and it is a staple on academic bookshelves as the 2005 recipient of the National Jewish Book Award. However, the idea of a Jewish mythology is not universally accepted, and the reasons do not include the myth as untrue canard. Most objections seem connected to the idea that Judaism is monotheistic and myths require gods that interact and even compete or conspire. Elie Wiesel, one of the best modern-day tellers of Jewish stories, makes his point about Jewish mythology in Messengers of God: Biblical Portraits and Legends. Many of Wiesel’s retold Jewish stories come from biblical and midrashic texts, the same sacred texts used by Schwartz. But, according to Wiesel’s introduction, the stories are not myth:

Jewish history unfolds in the present. Refuting mythology, it affects our life and our role in society. Jupiter is a symbol, but Isaiah is a voice, a conscience. Mars died without having lived, but Moses remains a living figure. The calls he issued long ago to a people casting off its bonds reverberate to this day, and we are bound by his Law. Were it not for his memory, which encompasses us all, the Jew would not be Jewish, or more precisely, he would have ceased to exist.1

So while the same stories refute mythology for Wiesel, they are mythology for Schwartz. He establishes these founding stories as Jewish myth in spite of the fact that Judaism is monotheistic. In looking at the permutations of Jewish myth, Schwartz reveals a dialectic evolutionary process “that alternates between the tendency to mythologize Judaism and the inclination to resist such impulses” (xxxiii).

The questions remain: Is Tree of Souls a book for Latter-day Saints? Do these stories, myth or not, have relevance to our stories? Comparing one Jewish tradition with a Book of Mormon narrative and other LDS traditions will give an answer.

After the brother of Jared prepares his eight vessels, each with two holes for air, he fashions sixteen stones from mount Shelem, a place that is not referenced in the Bible, but in Hebrew Shelem as used in Amos 5:22 means “peace offering.” The brother of Jared asks the Lord to touch the clear white transparent stones so that they will “shine forth in darkness” (Ether 3:4), a phrase that could symbolically represent the gospel that will be preserved by the journey to a new land and continue to shine forth.

The sixteen stones may be Tzohar. The story in Ether echoes the flood narrative in Genesis 6:16 when Noah is instructed to make a cubit-sized window in the ark. In Hebrew he “put the Tzohar in the ark” (85), which is much more than an opening or “window” as translated in the King James Version. To summarize the mythic trajectory of Tzohar, or sacred light, it was created when God said “let there be light” (Gen. 1:3). Tzohar is the light of creation, but different from the light created later on the fourth day in connection with the sun, moon, and stars. Tzohar comes to represent exactly what Latter-day Saints already believe about the gospel light or “light of Christ” that enlightens us all.

In mythic tradition, Tzohar is sacred and is fully entrusted to worthy prophets for the benefit of all. Adam and Eve lose Tzohar at the Fall but receive part of it again in the form of a stone from the angel Raziel after their expulsion from the garden. Adam gives the Tzohar stone to Seth on his deathbed. Seth passes the light to Enoch who in turn gives it to Methuselah. Lamech, Methuselah’s son, delivers the sacred light to Noah who uses it in the ark but loses it while drunk after the ark has landed. The trajectory of the sacred light continues as the stone is possessed by Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph (85–88).

Myth says that Jacob had the light stone when he had the ladder dream, and the stone saved Joseph from snakes when his brothers threw him into a pit. Later, Joseph put the stone in the cup that he hid in Benjamin’s sack. It was in the cup because Joseph used it and the cup for divination. “Is not this it in which my lord drinketh, and whereby indeed he divineth?” (Gen. 44:5). Does not the Tzohar myth resonate with LDS traditions of translation, light, stones, and restoration of truth?

That cup, with the precious jewel in it, was placed inside Joseph’s coffin at the time of his death, and it remained there until Moses recovered Joseph’s coffin and was told in a dream to take out the glowing stone and hang it in the Tabernacle, where it became known as the Ner Tamid, the Eternal Light. And that is why, even to this day, an Eternal Light burns above every Ark of the Torah in every synagogue. (86)

Doctrinally and metaphorically speaking, Latter-day Saints would say that Tzohar passed through a period of apostasy until it was restored through priesthood authority. In my reading of Schwartz, a light has also passed to a student of Jewish mythology and we now have in Tree of Souls an encyclopedic retelling of the sacred stories in a new, well-organized academic light.

The Tzohar is only a small niche lasting a few pages in this 618-page reference book. LDS readers will perk up at many stories about the physical attributes of God that include breath, mind, eyes, face, arms, hands, and body. And together we can wonder where these physical attributes are in modern Jewish thought and find comfort in understanding where they are in LDS theology. LDS readers will no doubt pause to read stories of the bride of God, the translation of Enoch, Elijah the angel, the ascent of Moses, stories of the Abrahamic covenant including Abraham’s glowing stone, the various stories surrounding the akedah (the binding of Isaac), numerous Sabbath tales, dozens of accounts regarding sacred garments including those of Adam and Eve, and an entire section of Messiah stories. With almost seven hundred carefully documented and explicated stories, the book seems to warrant a permanent place on a reader’s desk or nightstand.

In spite of some readings that seem to make no sense from our cultural context and some that seem to contradict each other as well as LDS tradition, most invite further discovery and support our natural instinct to see the light of congruence and explanation within a restored LDS worldview. This congruence makes academic and spiritual sense if what Harold Bloom says about Joseph Smith is correct: “What is clear is that Smith and his apostles restated what Moshe Idel, a great living scholar of Kabbalah, persuades me was the archaic or original Jewish religion, a Judaism that preceded even the Yahwist, the author of the earliest stories in what we now call the Five Books of Moses.”2

About the author(s)

Roger G. Baker is Professor of English, emeritus, at Brigham Young University and is the author of The Bible as Literature: Out of the Best Book (Ephraim, Utah: Snow College, 1995).

Notes

1. Elie Wiesel, Messengers of God: Biblical Portraits and Legends, trans. Marion Wiesel (New York: Random House, 1976), xi–xii.

2. Harold Bloom, “The Religion-Making Imagination of Joseph Smith,” Kingsbury Hall, University of Utah, 1990; Bloom, “The Religion-Making Imagination of Joseph Smith,” in The American Religion: The Emergence of the Post-Christian Nation (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992), 96–111; or Bloom, “The Religion-Making Imagination of Joseph Smith,” Yale Review 80 (1992): 26–43.

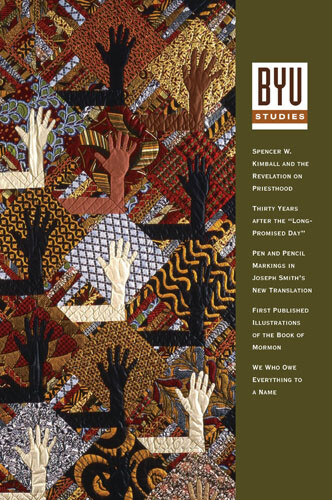

- Spencer W. Kimball and the Revelation on Priesthood

- The Nature of the Pen and Pencil Markings in the New Testament of Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible

- A Picturesque and Dramatic History: George Reynolds’s Story of the Book of Mormon

Articles

- Tunica Doloris

- Fifth-Floor Walkup

Poetry

- The Great Transformation: The Beginning of Our Religious Traditions

- Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism

- From Persecutor to Apostle: A Biography of Paul

- Wounds Not Healed by Time

- History May Be Searched in Vain: A Military History of the Mormon Battalion

- The Civil War as a Theological Crisis

- Before the Manifesto: The Life Writings of Mary Lois Walker Morris

- The J. Golden Kimball Stories

- Hooligan: A Mormon Boyhood

- Big Love, seasons 1 and 2

- The Dance

- Minerva Teichert: Pageants in Paint

Reviews

Purchase this Issue

Share This Article With Someone

Share This Article With Someone

The Great Transformation

Print ISSN: 2837-0031

Online ISSN: 2837-004X