Tom and Bessie Kane and the Mormons

Article

-

By

Edward A. Geary,

Contents

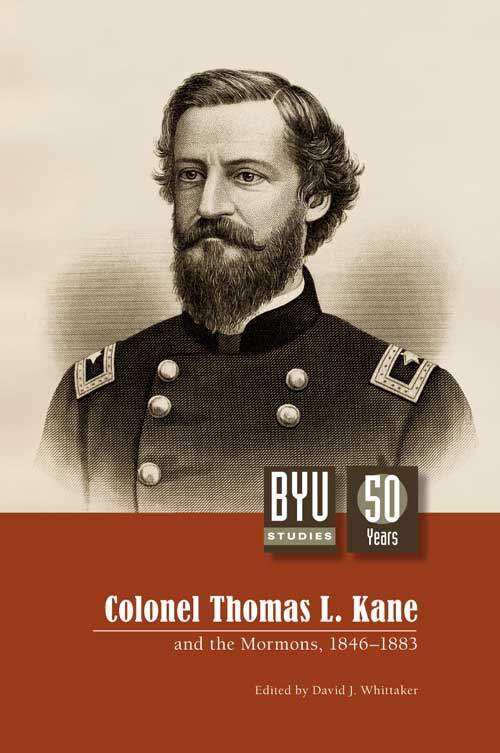

Thomas L. Kane and Elizabeth Dennistoun Wood—“Tom” and “Bessie” in their personal relationship—were united during their thirty years of marriage by intelligence, idealism, and deep mutual affection (figs. 1 and 2). However, they were divided by temperament and personal philosophy. Tom was ambitious yet burdened by a sickly constitution, resistant to religious and social orthodoxies yet preoccupied with his own social status and personal reputation; he was a compulsive risk-taker, indifferent to prudential considerations. Bessie was deeply religious, devoted to home and family, and hungry for emotional and social security. Tom wanted to change the world through heroic action and was driven to espouse the causes of oppressed or reviled groups, including women, the urban poor, slaves, juvenile offenders, and Mormons. Bessie shared Tom’s interest in improving the world by elevating the status of women but sought to accomplish the goal through unostentatious Christian service and a reform of social and sexual mores.

Although differing in perspective and approach, Tom and Bessie left their imprint on the history of the Latter-day Saints. Tom did so through his many years of devoted service, while Bessie contributed, more reluctantly, through a landmark literary treatment of nineteenth-century Mormon society.

The Kanes’ involvement with the Latter-day Saints is too extensive to examine in detail here. Instead, this article focuses on representative elements of key episodes in which they interacted with the Mormons. First I will briefly discuss Tom’s visit with the exiled Saints in 1846 and his subsequent activities that culminated in the delivery and publication of his influential lecture that was published as The Mormons in 1850 as well as his reaction to plural marriage in 1851; then I will explore Tom’s assistance during the Utah War in 1857 and 1858 and Bessie’s journals from the Kanes’ 1872–73 visit to Utah, published as Twelve Mormon Homes (1874) and A Gentile Account of Life in Utah’s Dixie (1995).1

A Brief Overview of the Kane Family

Tom and Bessie Kane were second cousins. Their common great-grandfather, John O’Kane, emigrated from Ireland to New York in 1752; dropped the Irish “O” from his name; married Sybil Kent, the daughter of a prominent clergyman; became a prosperous farmer; and sired a large family. When the American Revolution broke out, John Kane remained loyal to the British Crown, with the result that his properties were confiscated and his family forced to spend the war years as refugees in Nova Scotia. Following the war, the family returned to New York, where the sons established a trading firm that prospered until the disruption of transatlantic commerce by the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812. Bessie’s grandfather, John, managed the firm of Kane and Brothers in New York, while Tom’s grandfather, Elisha, established a branch in Philadelphia. The sons and daughters married well, uniting the Kanes with such prominent American families as the Livingstons, Morrises, Schuylers, and Van Rensselaers.2

Tom’s father, John, adopted his stepmother’s family name, Kintzing, as his own middle name to distinguish himself from several cousins also named John. John Kintzing Kane (fig. 3) received a classical education in Philadelphia schools, added a degree at Yale, and then returned to Philadelphia for legal training. He was admitted to the bar in 1817 and began a determined and ultimately successful courtship of Jane Duval Leiper, whose father, Thomas Leiper, was a prominent Philadelphia industrialist. The family into which Thomas Leiper Kane was born on January 27, 1822, has been aptly characterized as “politically powerful and socially aspiring.”3 The family did not possess great wealth, but they lived comfortably (though with periodic money worries) on John K. Kane’s income from his law practice and from a series of political appointments.4

The chief instrument of John K. Kane’s political influence was a skillful pen. The larger American cities had dozens of competing newspapers, most of them aligned with a political party, and all of them eager for material.5 John K. Kane supplied the papers that supported the rising Democratic Party with numerous unsigned articles reflecting his capacity “to influence, inspire, and use public opinion.”6 In addition, he published an influential pamphlet during Andrew Jackson’s 1828 presidential campaign titled A Candid View of the Presidential Question that portrayed Jackson in heroic terms while offering a much less flattering portrait of his opponent, John Quincy Adams.7 In 1844, John Kane turned his talents to the service of James K. Polk and his running mate, George Dallas, who was a personal friend, publishing a campaign biography, helping to draft Polk’s messages to Congress, and being rewarded, in 1846, with an appointment to the federal bench.8 John Kane further extended his social influence as a prominent Freemason and for many years as secretary and finally president of the American Philosophical Society.9

Unlike his father, who followed a steady career path, Tom Kane was driven in his early years by a restless ambition, an intense idealism, and frustrating personal limitations that included an undersized frame, frequent bouts of incapacitating illness, and periods of depression that he characterized as “blue devils.”10 His formal education ended at age seventeen when he dropped out of Dickinson College following a student rebellion.11 After leaving college, he traveled to England and France in 1840 and visited France again in 1842–43. While there he had one brief encounter with Auguste Comté.12

Even though it is doubtful Tom entered the philosopher’s social circle, it does seem likely he discovered Comté’s writings while in Paris, probably on the second visit, and it is certain that Comté’s thought had an important influence on Tom’s intellectual development. Even after his early disaffection from the family’s Presbyterian faith, Tom retained a lifelong interest in religion. To his brother Elisha he confided an early aspiration

that I should make to me fame by a religion. You often saw me at work upon it. By Jove it was a grand scheme:—a religion suited to the 19th century—a religion containing in itself all things and influencing all things—conduct of life—of man, nation & government—emancipating women & slaves—industrial classes—a religion containing itself the principle of its own change and amelioration—finally a religion of movement.13

These early ideas must have resonated with Comté’s concept of a “religion of humanity,” not based on a belief in God or in universals, but on an application of scientific analysis to social problems. Comté coined the word “altruism” to express the obligation to serve others and place their interests above one’s own. The opposite of egoism, which places the self at the center, altruism accurately describes Tom’s particular brand of benevolence. Tom also found something appealing in the Catholic ascetic tradition as reflected in The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis. Later in life, Tom settled on his own version of nondenominational Christianity that included elements of these and other religious influences.

Tom’s wife, Elizabeth “Bessie” Dennistoun Wood, was born in Bootle, a suburb of Liverpool, England, on May 12, 1836, making her fourteen years younger than her future husband. Her mother, Harriet Amelia Kane, was the youngest daughter of John Kane, who was the eldest and most influential of the Kane brothers. Her father, William Wood (fig. 4), a member of a family prominent in the Glasgow business community, was a merchant banker engaged in the cotton trade. Educated at St. Andrews and Glasgow universities, Wood was a free-trade liberal with wide intellectual interests and a trusted friend and confidant to Tom Kane long before he had any thought of becoming his father-in-law.

A biographical notice prepared by the family at Bessie’s death in 1909 states, “When she was six years old, she found her ideal in the gallant young cousin who . . . found welcome and healing in her father’s house. His kindnesses won her childish heart; and the French doll he gave her was never forgotten.”14 In fact, Tom probably first met Bessie during “a fortnight” he spent with the Wood family at Liverpool in July 1840. William Wood recalled him as an engaging young man, “full of mannerism, which, indeed, rarely left him even in after life.”15 Bessie would have been only four years old at the time of this meeting. Correspondence indicates that William and Harriet Wood did invite Tom to stay at their home while he recovered from his October 1840 foot injury.16 However, he chose instead to spend his convalescence at the Norfolk estate of a more distant relative, Archibald Morrison, where he remained through the winter.17 He probably visited the Woods before he returned home in spring 1841. Perhaps that is when he presented Bessie with the French doll. However, Bessie would have been scarcely five years old at this time, not six. On his second trip to Paris in 1843–44, Tom sailed directly from New York to Le Havre and did not visit England,18 so he would not have met the Wood family again until they moved to New York in July 1844, when Bessie was eight.

First Involvement with the Mormons

The year 1846 found Tom at a loose end; he did not find his new legal career satisfying. He wanted to become engaged in meaningful activities and chafed at the limited means and opportunities that constrained his range of action. In January, Tom’s father, who had been influential in President James K. Polk’s election, had been in Washington assisting with the preparation of the president’s message to Congress.19 Therefore, Tom would have been well aware of the president’s plans to extend the U.S. borders by settling the Oregon boundary dispute with Britain and compelling Mexico to cede California and New Mexico well in advance of the declaration of war with Mexico in May. The idea of going to California at such a momentous time appealed to Tom, who knew the Mormons had plans to relocate to the West. On May 13, he attended a Latter-day Saint meeting in Philadelphia, where he met Jesse C. Little, who oversaw Church affairs in the east.20

There was some ambiguity in Tom’s motives, and this complexity was evident in his initial involvement with the Saints. Depending on the motivational strand selected, it is possible to construct a convincing account of his actions based on altruistic compassion for a persecuted and driven people. However, it is equally plausible to account for his actions as having been motivated by self-interest. Tom viewed the westward-bound Mormons as a means to achieve his own ambitions for power and prominence, perhaps resulting in a federal appointment in California.21

It appears, however, that the Mormons constituted only one portion of Tom’s plans to achieve his ambitions. Having previously failed to secure a military commission,22 he was no doubt gratified when the Polk administration entrusted him with dispatches for Colonel Stephen W. Kearney as well as additional dispatches for California.23 Tom had wanted to travel directly to California from Fort Leavenworth. It was only after Kearney and William Gilpin advised Tom that he was too late to catch the season’s California emigration and that it would be too dangerous to attempt to cross the plains alone that he redirected his course northward to the Mormon camps on the Missouri River, arriving at Council Bluffs on July 11.24 He was disappointed when he learned the Mormons did not plan to go farther west in 1846 and that their ultimate destination was not the Sacramento Valley but the less politically vital Great Basin. At this point, he hoped he could establish a name for himself by writing a popular book about Mormonism.25

It is possible to construct yet a third version of Tom’s motives, suggesting he went among the Mormons, not as a disinterested benefactor, but rather as a government agent. Following an interview with President Polk, Tom wrote a letter to his brother Elisha, his closest confidant, declaring, “You must know that it has weighed upon my mind for months past whether it was not my duty to go with the Mormons, and this increased as I began to see signs of something which even to my eyes looked like English tampering with their leaders.” He then described his interview with the president, during which he told Polk “what I knew of the people and their leaders, and what I knew of H. B. [Her Britannic] Majesty’s interference—also my own peculiar position and means of influence, and then said that, if he thought it of enough importance that I should expatriate myself for a time and expose myself to risk and hardship, I would do so.”26 This was similar to what he later confided to Bessie during their courtship:

It was thus, after wasting no more time than was absolutely necessary to ingratiate myself with some Mormons in Philadelphia and procure my purposes to be misrepresented; invested with amusingly plenipotential powers civil and military, I “went among the Mormons.”

Bessie, this is a little State Secret. Mr. Polk knew it. General Kearney knew it. One Col. Allen detailed by Kearney to march off a Battalion knew it. But probably no one else.27

However duplicitous or self-promoting Tom’s initial motives may have been, his experiences in the Mormon camps appear to have transformed him. He presented himself as “Colonel Kane”—an honorary title he had seldom, if ever, used before this time—and was greeted warmly. He found the Church leaders to be “men more open to reason and truth plainly stated” than any others he had met and reported to his family “the most delightful relations subsist between the Twelve and myself. They are without any exaggeration a body of highly worthy men and they give me their most unbroken & childlike confidence.” To his parents he wrote, “I will devote much of time when I come home to the Mormons,” particularly to the “main task” of reshaping their public image. “If public opinion be not revolutionized,” he lamented, “the miserable dramas of [persecution against the Mormons in] Missouri and Illinois will be acted over again, with the alteration that there will be no country left to which the persecuted can fly.”28

In a letter written four years later to Brigham Young and his other Mormon friends, Tom described his initial encounter with the Saints in terms suggestive of religious conversion:

I believe there is a crisis in the life of every man, when he is called upon to decide seriously and permanently if he will die unto sin and live unto righteousness. . . . Such an event, I believe . . . , was my visit to [you]. . . . It was the spectacle of your noble self denial and suffering for conscience sake, [that] first made a truly serious and abiding impression upon my mind, commanding me to note that there was something higher and better than the pursuit of the interests of earthly life for the spirit made after the image of Deity.29

Although Tom never joined the Latter-day Saint faith, he clearly had an interest in the religion and the people.30 He knew the Book of Mormon and Doctrine and Covenants well enough to quote from them and to employ religious symbolism from their pages.31 Furthermore, he challenged his wife’s Presbyterianism by describing “the exceedingly miraculous powers” he had observed among the Mormons. “He has seen instances, scores of them, of invalids restored to health and working capacity by the word of the Mormon priest.”32 And he cherished throughout his life the blessing he received from Patriarch John Smith on September 7, 1846. Even Bessie was compelled to admit, years later, that this blessing “has been curiously fulfilled so far, strange to say.”33

Tom’s labor and personal sacrifice in support of Latter-day Saints were different from his many other altruistic and reform projects both in their extent—beginning at age twenty-six and continuing throughout his entire adult life—and the intensity of his personal engagement. Typically, Tom adopted an attitude of aristocratic responsibility, extending benefits derived from his privileged and influential social position to those lower on the social scale, be they slaves, youthful offenders, or Mormons. That characteristic attitude appeared in his work with the Latter-day Saints; however, it was mixed with a deeper engagement. Matthew J. Grow noted that, “unlike the objects of his other reforms, Kane could not keep an emotional distance from the—Mormons.”34

In its social dimensions, the Latter-day Saint religion exhibited some qualities Tom longed to promote. Mormonism was not just a ritualized Sunday religion: it involved all aspects of its members’ lives; it expressed an ideal of government in the concept of the Kingdom of God on earth; it melded converts from different social backgrounds into one community; and it contained within itself “the principle of its own change and amelioration” through the concept of continuing revelation.35 While he always viewed Mormons as his social and intellectual inferiors, Tom respected Brigham Young as a social genius, one of the great men of the age. Tom also developed a high personal regard for several other Latter-day Saint leaders, particularly George Q. Cannon (fig. 5). As Grow further declared, “Besides Kane’s immediate family, no one influenced the direction of his own life more than Young.” At the same time, Young relied on Tom as “his most trusted outside adviser” for three decades.36

The Mormons

When Tom returned home to Philadelphia in fall 1846, he continued his lobbying and public relations activities in support of the Saints. Employing the strategy his father had used so successfully in his political activities, Tom began by planting editorials favorable to Mormons in eastern newspapers. As he wrote to Brigham Young, “It was found next to impossible to do much for you before public opinion was corrected,” and so “it became incumbent on me to manufacture public opinion as soon as possible.”37 This campaign culminated in a public lecture, presented to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania on March 26, 1850, titled “The Mormons.” An expanded version of the lecture was published and then distributed to members of Congress and other public opinion makers.38

The Mormons, which Tom claimed to have written on his sickbed, reflected his strategic rhetorical skills. In his actual encounter with the Saints, he went first to the encampments near the Missouri River and then visited Nauvoo on his way home. However, The Mormons began with the visit to Nauvoo and suggested that he was a tourist with no prior knowledge of the Mormons. He described traveling up the Mississippi River through a dreary region. Suddenly, “a landscape in delightful contrast broke upon my view. Half encircled by a bend of the river, a beautiful city lay glittering in the fresh morning sun; its bright new dwellings, set in cool green gardens, ranging up around a stately dome-shaped hill, which was crowned by a noble marble edifice, whose high tapering spire was radiant with white and gold.”39

These opening paragraphs established a contrast sustained throughout the work. The Mormon city, like the Saints, reflected a higher standard of civilization than was to be found elsewhere on the Western frontier. Nauvoo and its environs exhibited “the unmistakeable marks of industry, enterprise and educated wealth,”40 but the homes, gardens, workshops, and fields had been abandoned, and the author found a drunken rabble in possession of the city. The last Mormon refugees were starving in camps on the Iowa shore while “those who had stopped their ploughs, who had silenced their hammers, their axes, their shuttles and their workshop wheels; those who had put out their fires, who had eaten their food, spoiled their orchards, and trampled under foot their thousands of acres of unharvested bread; these,—were the keepers of their dwellings, the carousers in their Temple,—whose drunken riot insulted the ears of their dying.”41

Tom’s image-making continued in the description of the Saints at Council Bluffs. The camps were “gay with bright white canvas, and alive with the busy stir of swarming occupants.” Herd boys were “dozing upon the slopes” while great herds of livestock grazed in the meadows. Beside a small creek, “women in greater force than blanchisseuses upon the Seine” were “washing and rinsing all manner of white muslins, red flannels and parti-colored calicoes, and hanging them to bleach upon a greater area of grass and bushes than we can display in all our Washington Square.”42 As he mingled with “this vast body of pilgrims,” hospitably received everywhere, the author declared, “I can scarcely describe the gratification I felt in associating again with persons who were almost all of Eastern American origin,—persons of refined and cleanly habits and decent language.”43 The message suggested the Mormons were very much like members of the author’s own audience, and very unlike “the vile scume” who lived in “Western Missouri and Iowa.”44

The author extolled the Mormons’ “romantic devotional observances,” their “admirable concert of purpose and action,” their “maintenance of a high state of discipline,”45 and the way in which their religion “mixed itself up fearlessly with the common transactions of their every-day life.”46 He also praised their patriotism for volunteering for the Mormon Battalion, as “the feeling of country triumphed” over a call that “could hardly have been more inconveniently timed.”47 In framing the enlistment in these terms, Tom contributed to the longstanding misconception among many Saints that the request for volunteers was one more unjust exaction by a society that had already subjected them to much suffering. Actually, the Mormon Battalion, as Kane well knew, was the government’s response to the Saints’ request for assistance in their journey west.

The final part of The Mormons described the journey to Utah and the establishment of a society there. Here, Tom’s chief source of information was the epistles from Church leaders directed to the Saints who had not yet gathered to Utah. These epistles were themselves exercises in the manipulation of public opinion and painted early Utah society in the most favorable terms.

The Mormons was soon reprinted by Latter-day Saint periodicals, both in England and in the U.S. The pamphlet has been quoted or paraphrased by many who were unaware of their indebtedness to Thomas L. Kane for the enduring images of the City Beautiful and the camps of Israel. Written for the purpose of shaping national public opinion toward the Saints, The Mormons arguably had a more powerful and enduring effect on the Saints themselves.

Polygamy: “This Great Humiliation”

In a second edition of The Mormons, issued in July 1850, the author added a postscript answering criticisms that had been levied against the original publication. Responding to claims that he had portrayed the Saints in too positive a light, Tom reaffirmed his judgment that they did not “in any wise fall below our own standard of morals” and displayed a “purity of character above the average of ordinary communities.”48 In answering rumors about Mormon polygamy, he emphasized “their habitual purity of life” and quoted a passage from what was then section 109 of the Doctrine and Covenants, which declared, “we believe, that one man should have one wife, and one woman but one husband.”49

This was not the only occasion in which Tom vouched for the monogamy of Mormons. When his good friend and future father-in-law, William Wood, asked him pointedly “Do the Mormons allow polygamy, or do they not?”50 Tom categorically replied in the negative. Wood wrote, “I am much pleased to have your testimony to the purity of the Mormons. I wanted to be able distinctly to contradict the accusations of their tolerance of Polygamy.”51

Then, on December 27, 1851, Tom received a visit from Jedediah M. Grant, a member of the Twelve, who sought Tom’s assistance in composing and placing newspaper articles to refute damaging allegations by non-Mormon Utah territorial officers. In the course of their discussions, Grant learned that Tom did not know the Saints had been practicing plural marriage. Even though he had been welcomed by the Saints on the Missouri as a trusted friend, they had not revealed to him their peculiar marital practices.52

Because of his emphatic denials of the polygamy rumors, this information was devastating to Tom. On December 27, he wrote, “Heard this day first time Polygamy at Salt Lake.” The following day he added, “This I record as the date of this great humiliation, and I trust final experience of this sort of affliction. . . . Similar doubtless to discovery of wife’s infidelity.”53

Two days after learning of polygamy, Tom drafted a letter to John M. Bernhisel, the Utah territorial delegate to Congress, saying, in part:

Mr. Grant has made me for the first time acquainted with a state of facts at the Salt Lake which puts it out of the power of the Mormon people any longer truthfully to refute the accusation of their enemies that they tolerate polygamy or a plurality of wives among them. It is not my place here to express the deep pain and humiliation given me by this communication for which I was indeed ill prepared.

Tom went on, however, to reaffirm “the relations of personal respect and friendship” toward Bernhisel, “the more so that I understand you have grieved with myself at this intelligence.”54

Several months passed before Tom wrote to Brigham Young. In the interim, Tom continued to assist Jedediah Grant in his public relations campaign and also lobbied the government for the appointment of a new federal judge for Utah Territory. During this time, however, Tom seemed to be thinking of discontinuing his work for the Mormons. He wrote to William Wood in May 1852 declaring his recent efforts to be “my last labor of the kind” and expressing the hope that Bessie Wood (to whom he was by then engaged) would not see the newspaper articles he had helped Grant to prepare.55

Writing to Brigham Young in October 1852, Tom explained the delay in his communication by reporting the illness and death of his youngest brother, Willie. Tom broached the topic of polygamy in terms that expressed both a personal and an intellectual disappointment:

I wish to thank you for making my old friend Grant the bearer to me of his tidings. I ought not to conceal from you that they gave me great pain. Independent of every other consideration, my Pride in you depends so much on your holding your position in the van of Human Progress, that I so grieve over your favor to a custom which belongs essentially, I think, to communities in other respects behind your own.

In other words, the Mormons had, in Tom’s estimation, betrayed their potential as “a religion for the 19th century” by adopting a retrograde social model. He predicted an adverse impact on “female education, the concord of households, the distribution of family property, and the like,” from the practice of polygamy. At the same time, he reaffirmed his personal regard for Young, a friendship that made his present frankness possible:

I have not yet been disappointed in treating you as a Man, able and accustomed to look and speak to Men in the face. You understand me now as you have understood me hitherto, and have it in your power to accept understandingly the friendship of which I also understandingly offer you the full continuance. I think it my duty to give you thus distinctly my opinion that you err. I can now discharge you and myself from further notice of the subject.56

Notwithstanding these friendly assurances, it appears that Tom’s labors in behalf of the Mormons were significantly reduced from 1852 to 1857. In December 1857, Bernhisel remarked to one of Tom’s friends, “Of late years [Tom] has treated us very coldly; we think on account of our religion.”57 Bessie later noted that while her husband was rightly believed “to know more of the personal character of the Mormon leaders than any other Gentile,” he was “completely deceived for years as to the practice of polygamy, and I can well remember his difficulty in believing that it did exist, or in keeping up his friendship for the Mormon leader when he realised it.”58

Tom and Bessie’s Courtship and Marriage

Tom’s reduced involvement with the Saints corresponded with the period of his courtship and marriage. Tom had known Bessie from the time she was a young child, and family tradition holds that she had settled on him as her future husband by the time she was twelve.59 Serious courtship began in early 1852, and they were married on April 21, 1853, when Tom was thirty-one and Bessie three weeks shy of seventeen.

Bessie’s mother died in 1846, the year Bessie turned ten and the year Tom first worked among the Mormons. Thereafter, “for seven lonely years, she found comfort and companionship with her studies and poets, brightened by occasional glimpses of her idolized cousin. At twelve she said once to her sister, ‘Why, I thought you all knew, I intend to marry Cousin Tom Kane!’”60

That intention was strengthened by an 1850 visit Bessie and her elder sister Charlotte paid to the Kane home in Philadelphia. In a love letter written two years later, she recalled listening to Tom playing the piano and singing, feeling “that though you were so very dear to me, you never would love me.”61 Sometime later, Tom joined the Wood family for several weeks at Newport. Bessie recalled an excursion to a teahouse where he “walked on the piazza with me, and spoke of the kind of husband I would marry,” after which “I lingered behind [him] a step, that I might see the face of the one I had resolved to win!”62

Bessie and Tom arrived at a personal understanding in January 1852, when she was fifteen and he approaching thirty. They informed her father of their attachment in March 1852, but they did not tell Tom’s parents until sometime later. William Wood wrote, “It is a pity that Bessie is so young, not that I think there would be the slightest chance of her changing her mind, if she had seen more of the world, nor in my opinion could she have chosen better had she been 32 instead of 16.” He added, “Bessie from childhood has jumped into womanhood, instead of passing gradually from the one condition to the other.”63 Probably with the intention of slowing the advance of the couple’s feelings, Bessie’s father took her on an extended trip to England, Scotland, and France in summer 1852. Most of their courtship letters were written then.

Bessie was intellectually mature beyond her years (figs. 6 to 10), well read and articulate, but she displayed the intense emotional ups and downs of an adolescent.64 She expressed the fear that her love for him amounted to idolatry “because you know we ought to have our treasure in Heaven, and I am afraid mine isn’t there.”65 She wrote of her consciousness of “my inferiority to you” and begged him to take control of her education.66

Tom’s letters were typically shorter and included reports on the condition of his dying brother, Willie, as well as more restrained declarations of love. When he did write at greater length it was to express his plans for the future: for a new country retreat, Fern Rock, to be built in an idyllic setting north of Philadelphia, or, more idealistically, for a lifetime of altruistic service.67 In reply, Bessie wrote of visiting the poor districts in Glasgow to prepare herself for the career Tom envisioned. “I hope I shall get accustomed to seeing such people without feeling disgusted. . . . If you let me begin gradually, don’t you think I could come to sympathise with them and love them?”68 It seems likely that Bessie interpreted Tom’s plan as a life of Christian service, while he was thinking along the lines of Comté’s “religion of humanity.”

Bessie’s stepmother considered it improper for her to marry at such a young age.69 However, William Wood gave his permission for the marriage on November 25, but stipulated, “I think it would sound better to the world in general if you allowed Bessie to pass her 17th birthday (12 May 1853) before she was married.”70 Tom and Bessie were married on April 21, 1853, three weeks before she turned seventeen.

The newlyweds initially lived in a rented house next door to the Kane family in Philadelphia. After a few months, the couple moved in with Tom’s family, spending winters with them in the city and summers at the new country house, Fern Rock. They would not have a home of their own until they moved permanently to the Allegheny Mountains following the Civil War.

Bessie struggled to adjust during the first few years of marriage. Having grown up in a rather puritanical home, she was somewhat taken aback by the free-thinking and free-speaking Kanes, noting in her journal on one occasion, “Half the family [would] fly the dinner table in a passion—I supposed they were parted forever. But at the tea-table there they all were, cheerful and kind as if nothing whatever had happened to be forgotten or forgiven.”71

Bessie’s passionate devotion for Tom never wavered, but she was disappointed that he refused to attend church with her, and she was concerned that so large a portion of his earnings sustained his benevolent activities instead of building a financial foundation for his own family. She also believed the Kane family failed to appreciate Tom’s qualities but instead dwelt on the failures of his grandiose plans.

After the birth of Harriet Amelia (named for Bessie’s mother) and Elisha Kent (named for Tom’s brother and his grandfather), Bessie settled more comfortably into family life, even though some tensions remained. Tom desired to make their marriage a model for reform and, ironically, tended to dominate his wife in the interests of gender equality. He pressed her to enroll in the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania (see fig. 11), for which he served as a “corporator” (trustee). She studied off and on for years, finally earning an MD degree in 1883.72

The year 1857 was an especially difficult time with the death of Tom’s beloved elder brother, Elisha, and the business failure and nervous breakdown of Bessie’s father.73 It was during this period that Tom once again felt pressed to sacrifice his personal and family interests to give aid to the Mormons.

The Utah War

Tom’s role in bringing the 1857–58 conflict between the federal government and the Latter-day Saints to a peaceful resolution has been extensively treated by other authors, including William MacKinnon’s essay herein. My only intentions here are to emphasize the sacrifices required of Bessie by her husband’s hazardous expedition and to highlight the importance of Tom’s strategic rhetorical skills in his mediation efforts.

Tom’s family was strongly opposed to his planned mission. On the eve of his departure, he resigned his position as clerk of the U.S. district court, leaving his wife without an income and with uncertain future prospects. The money he left was quickly exhausted as he had characteristically underestimated the amount of every obligation,74 leaving her “to eat the bread of Dependence, bitterer than gall.”75 Her circumstances became even more difficult when Tom’s father died in February 1858 following a short illness.

Bessie was sustained through all these trials by the information her husband had confided to her before his departure; he had expressed his readiness to become a Christian. When Bessie wrote of the “horrors we have passed through,” she then added, “God has mercifully brought out of them one great blessing already, in uniting Tom and me in the bonds of a common faith.” Strengthened by this assurance, she was willing to consign her husband into God’s hands “to bring peace to those lost Sheep of Israel.”76

The hope that had sustained Bessie during her husband’s absence was abruptly terminated upon his return home on June 20, 1858: “Tom told me the first moment we were alone, like my dear honest darling, that the hope that had dawned on him of being a Christian is gone.”77 It was hardly surprising that Bessie should have blamed the Mormons for blighting Tom’s budding faith, though there was no indication he made such an attribution. (It seems equally possible that his grief at his father’s death could have been a decisive factor.) Still, these events intensified Bessie’s longstanding grudge against the Mormons, especially Brigham Young.

Tom’s skill at manipulative rhetoric appeared in the documents he prepared as part of his mediation efforts. While his actions were at times foolhardy, his writing was well calculated. He knew President Buchanan was firmly convinced the Mormons were in a state of active rebellion. Rather than attempting to refute that view directly, Tom constructed an image of the Mormons as divided between a war party and a peace party, with Brigham Young serving as the leader of the peace party. In a letter to the president, Tom asserted that it was of the greatest importance to “strengthen the hands of those—and they are not few here—who seek to do good and whose patriotism is as elevated as any which labors elsewhere to confirm the bands of the Union.” He continued, “From the commencement nearly of the unhappy difficulties between Utah and the United States, [Brigham Young’s] commanding influence has been exercised to assuage passion, to control imprudent zeal, and at all risks, either of his own person or that of others, to forbid and ensure a just condemnation for bloodshed.”78 After arriving at the army encampment, Tom sent another letter in which he described the previous one as “the joint composition of an eccentric great man and myself.”79

Evidently, Tom enclosed the letter to the president in another letter to his father, in which he asked his parent to assist in this public relations campaign by publishing Tom’s information in a suitable form in newspapers such as “the Episcopal Recorder, or the Observer of New York.” This article was to emphasize the human suffering Mormon women and children would face if forced to flee from their homes into the wilderness. While the innocent would suffer, “the leading heresiarchs” would “instigate resistance as long as it was perfectly safe to do so, and then retire disguised at their pleasure toward any one of the points of the compass.” The article also would pose the question, “What will be the fate of the real abominable thing which we ought to wish shd. perish.—the evil Religion itself—the Mormonism.” He would argue that persecution would only increase the appeal of Mormon missionaries abroad: “What a clover of female approbation the Mormon lecturer will delight in who appears before his British audience ‘in deep black’ for his murdered family.”80

Fortunately for the outcome of Tom’s mission, he and the new territorial governor, Alfred Cumming, took a liking to each other, quite different from the mutual animosity between Tom and the military. He drafted several letters for the governor, some to federal officials and others to the citizens of Utah, in which he further consolidated his image-making of the conflict—and, not incidentally, he accomplished some self-promotion as well. However, in his aristocratic pride he refused to capitalize on his fame as a peacemaker by writing a book on his experiences, nor would he allow either the federal government or the Mormons to reimburse the expenses of his journey.81

The Kanes’ Visit to Utah

There were relatively few contacts between Tom and the Mormons during the 1860s. When the Civil War began in 1861, Tom’s idealism and impulsiveness drove him to volunteer for immediate service. At his own expense, he enlisted a regiment of volunteers from the Allegheny region (commonly known as the “Bucktail Regiment” because the soldiers affixed a deer tail to their hats).82 Tom was shot in the face at Dranesville, wounded in the leg and captured at Harrisonburg, and commissioned as brigadier general for gallant service at Catlett’s Station and the second Battle of Bull Run. He left his bed in a Baltimore hospital, where he was suffering from pneumonia, to take command of his brigade on Culps Hill at the Battle of Gettysburg, even though he was too weak to sit on his horse. Following a stern warning by his physician that his mental and physical constitution would not survive another battle, Tom resigned from service on November 7, 1863.83

Following Tom’s resignation, the family returned to McKean County in the Allegheny Mountains where, despite the continuing effects of his war injuries, Tom developed the timber resources, recruited settlers, promoted railroad construction, and established the town of Kane. While the Kanes owned a substantial acreage and managed additional lands, the area’s development went forward slowly and did not provide the family with financial security until near the end of Tom’s life. After his death, the development of oil resources brought prosperity to Bessie and her family.84

Tom again initiated correspondence with Brigham Young in 186985 and resumed lobbying efforts for the Latter-day Saints, working against the series of antipolygamy bills that were being introduced in Congress. In response to Young’s invitations to visit Utah for consultations, Tom replied, “I still persuade myself that I will come out before I die and complete the collection of my materials for the Life of Brigham Young. I often cheer myself with a vision of pleasant weeks to be spent in your company—when—our minds both free from the common cares which now compel our thoughts—our converse shall turn as of old on higher things.”86 In light of his personal aversion to polygamy, it is interesting that in advising the Church leader on strategies for achieving Utah statehood, Tom cautioned Young not to pretend to adopt any policy the Church was not willing to comply with in reality: “Duplicity, I see, without a shadow, will not be a good policy for you.”87

Bessie did not share her husband’s renewed interest in the Mormons, nor did she wish to travel to Utah. Adding to her longstanding resentment of the Mormon influence on Tom was her awareness that the developments at Kane were at a critical stage that required his full attention. She agreed to the trip only when the proposal of a visit during winter 1872–73 opened the prospect of Tom’s escaping the rigors of the season in western Pennsylvania.88

At age thirty-six, Bessie was a more confident and independent woman than the vulnerable young wife who had seen her husband depart for Utah in 1858. Now the mother of four children (fig. 12), she assisted in the management of Tom’s business affairs with a more practical head for business than he possessed. She had initially undertaken medical studies because Tom wanted her to be an example of what education could do for a woman. As she intermittently pursued work toward her degree, in addition to her family responsibilities, she discovered that her skills were both useful and empowering in the medically underserved region around Kane. Bessie also had developed an interest in women’s rights and had begun the temperance work to which she would devote her later years. Most importantly, while she still loved Tom, she depended less on his judgment and had achieved a genuine intellectual independence. These qualities shine through her writings on the Mormons.

Bessie’s account of her experiences initially took the form of journal entries and letters to her family. After returning home, Tom encouraged and assisted her in publishing these in hopes a book would assist in his lobbying efforts against the antipolygamy Poland Act, which was then before Congress.89 The result was a slender volume, published in 1874, titled Twelve Mormon Homes Visited in Succession on a Journey through Utah to Arizona, as discussed by Lowell C. Bennion and Thomas Carter’s essay herein.

The book appeared with a secondary title page that read, “Pandemonium or Arcadia: Which?” Bessie also used this phrase, in inverted order, near the end of her St. George journal:

Farewell, Arcadia!

Or Pandemonium—Which?90

At the most obvious level, she used this phrase as a rhetorical device to emphasize paradoxical images of the Latter-day Saint religion and society. Pandemonium is the name coined by John Milton for the city built by Lucifer and his fallen angels in Paradise Lost. Bessie used it to reflect the demonizing of the polygamous and theocratic Mormons by much of the national political establishment, the press, and zealous Protestant religionists, including her fellow Presbyterians. This image was additionally reinforced by a line from John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, which Bessie uses as an epigraph: “As I walked through the wilderness of this world, I lighted on a certain place where was a den.”91 The image of Mormondom as a den of iniquity is also reflected in the letters friends from home had written, urging her to hasten away from “those dreadful Mormons.”92 Arcadia, originally a pastoral district in ancient Greece, later became a literary figure for an idealized existence of rural seclusion, characterized by a natural virtue free from the contaminating influences of urban society. In Bessie’s usage, Arcadia evoked the image of the western Zion as a refuge from worldliness, an image promulgated by nineteenth-century Latter-day Saint missionaries in the United States and Europe. The implicit answer offered in both Twelve Mormon Homes and the St. George journals is that Mormon country was neither Pandemonium nor Arcadia but, like any human society, contained a mixture of positive and negative aspects.

At a deeper level, Bessie’s question reveals her unresolved ambivalence toward the Mormons. Secure in her own religious faith, she had little interest in Latter-day Saint doctrines and found their claims to religious authority offensive. She might have taken an interest in Mormon social experiments aimed at eliminating poverty and creating a more egalitarian community had those experiments not included plural marriage. She also felt the Mormons had claimed too much of her husband’s life, had prevented him from attaining the social distinction he otherwise might have enjoyed, had drained resources that could have contributed to strengthening his own family’s security, and—worst of all—had somehow prevented him from sharing her own devout Christian faith. And yet, because Tom was devoted to the Mormons, and Bessie was devoted to Tom, she could not dismiss a cause he valued.

Aside from the political strategy involved in the publication and distribution of Twelve Mormon Homes “with the design of commanding sympathy for the Mormons, who are at this time threatened with hostile legislation by Congress,”93 Bessie’s rhetoric, unlike her husband’s, was not essentially strategic. Where Tom’s prose seemed always to be calculating the effect of his words upon a reader and to be primarily concerned with shaping a public image, Bessie’s work was characterized by a sincere and steady effort to report the truth of her own impressions and judgments. The quest for honesty included a sustained attempt to record the thoughts and feelings of the Mormons—particularly the Mormon women—in their own voices. Bessie frankly acknowledged her own social missteps and the prejudiced views she was compelled by her experiences to renounce or revise, and she used a lively wit and a sense of irony to underscore her own weaknesses and those of others.

Bessie’s attitudes toward the Mormons were softened, first, by the great affection and respect they displayed to Tom. In Utah, everyone seemed to hold him in the same high regard as she did. Thus, for Tom’s sake, she tried to get to “know and appreciate his poor friends.”94 This was often easy to do, such as in the case of William Staines (fig. 13), who had been Tom’s host in 1858 and who became a favorite with Bessie and her young sons. She described the man as “the deformed gentleman [Staines had a hunched back] whose earnest simplicity and sincerity have struck me, as much as his kindness has done the children. He is the only Mormon man with whom I have more than a passing acquaintance.”95

Although Brigham Young treated her with great courtesy, Bessie could not overcome her resentment against him as the chief representative of all she found objectionable in Mormonism. And yet she tried to do him justice in her writings and ended up providing one of the best portraits of this man in action. Bessie remarked on the “characteristic look of shrewd and cunning insight” and noted, “His photographs, accurate enough in other respects, altogether fail to give the expression of his eyes.”96 She appreciated Young’s generosity in giving the Kanes his luxurious city coach to travel in. When the driver of a heavy wagon from the Nevada mines deliberately drove into their coach, damaging a wheel hub, she acknowledged the calm dignity with which Young received the offender’s apology, aware that her impetuous husband would not have shown such restraint.97

At each stop along the route to St. George, Bessie observed with interest the “informal audiences” during which Young received the “reports, complaints, and petitions” of local residents. In an incisive passage, she wrote:

I think I gathered more of the actual working of Mormonism by listening to them than from any other source. They talked away to Brigham Young about every conceivable matter, from the fluxing of an ore to the advantages of the Navajo bit, and expected him to remember every child in every cotter’s family. And he really seemed to do so, and to be at home, and be rightfully deemed infallible on every subject. I think he must make fewer mistakes than most popes, from his being in such constant intercourse with his people. I noticed that he never seemed uninterested, but gave an unforced attention to the person addressing him, which suggested a mind free from care. I used to fancy that he wasted a great deal of power in this way; but I soon saw that he was accumulating it.98

After hearing him speak at a meeting in St. George, Bessie reflected, “Poor Brigham Young. With such powers, what might he not be but for this Slough of Polygamy in which he is entangled!”99 She also was critical of his economic policies, particularly the emphasis on “home industry” and self-sufficiency, which she believed had brought unnecessary suffering to the “saints who had been told off to Southern settlements where the desert had failed to blossom as the rose” and who were “expected to show their faith in Providence by flying in the face of Adam Smith.”100 And she remained startled when she realized Young, so full of practical wisdom, actually believed the incredible doctrines of Mormonism. Hearing reports in St. George of the rise of a Paiute “prophet” in Nevada, Bessie asked Young his opinion of the man. He replied:

No, it was only tags and scraps of old Mormon teaching that the man had picked up. If he was genuinely inspired—of course he would have been inspired to come at once to him, Brigham Young.

Brigham Young is so shrewd and full of common sense that I keep forgetting he is a Mormon himself, and this answer, so natural a one from his point of view took me completely aback. I felt as if I had asked one lunatic his opinion of another!101

Clearly, Bessie’s biggest problem with Young was his support of plural marriage. During the journey to St. George, she became well acquainted with “Delia,” one of the leader’s youngest wives, condemned (as Bessie saw it) to serve as a nurse to her husband in his declining years. She wrote, “I pitied Delia from the depths of my soul!”102

In Twelve Mormon Homes, Bessie made an effort to disguise the identity of most of the Mormons who practiced plural marriage. However, it is easy to penetrate the disguise as she made her sharpest indictment of Brigham Young. When “Delia” affirmed her faith in the divinity of plural marriage, Bessie reacted strongly:

How I detested her husband as she spoke! I felt sure he could not believe that that was a divine ordinance which sacrificed those women’s lives to his. I heard him say that when “Joseph” first promulgated the Revelation of Polygamy he “felt that the grave was sweet! All that winter, whenever a funeral passed,—‘and it was a sickly season’—I would stand and look after the hearse, and wish I was in that coffin! But that went over!”

I should think it had gone over! He has had more than half a dozen wives.103

Bessie had come to Utah in hopes that the polygamy problem might be solved by encouraging Congress to pass a law that would recognize the legitimacy of existing plural marriages while prohibiting the contraction of future polygamous unions. To her surprise and dismay, she found that every polygamous wife to whom she presented this idea vehemently rejected it as making a mockery of their faith and their personal sacrifices. To Bessie’s suggestion that such a law would secure these women’s social positions, “Delia” replied, “How can that satisfy me! I want to be assured of my position in God’s estimation. If polygamy is the Lord’s order, we must carry it out in spite of human laws and persecutions. If our marriages have been sins, Congress is no viceregent of God; it cannot forgive sins, nor make what was wrong, right.”104

As Bessie’s hopes for a legislative solution ran aground on the firm resistance of the Mormon women, her view of the Saints’ future became more pessimistic. She envisioned a time when effective antipolygamy laws would either destroy the Mormon community entirely or send its members once again fleeing, with either result bringing immense suffering to the innocent. When the elderly Lucy Young fervently affirmed her faith that God would protect the Saints in their mountain sanctuary, Bessie reflected, “It is hard to set down this faith of hers that God was taking care of them as a fancy: especially as I want to believe that He watches over me in the same special sort of way.”105 Ultimately, Bessie fell back on the hope that “more than one Mormon woman sees that such an intimate friendship such communion of mind and heart as is possible between a man and his one wife, cannot subsist in polygamy. My happiness is a stronger missionary sermon than anything I could say by word of mouth.”106

Despite her concerns, Bessie acknowledged that women enjoyed some advantages in Mormon society. After observing a highly professional inspection of the female-staffed telegraph office in Lehi by a female inspector from Salt Lake City, Bessie wrote, “It was an example of one of the contradictions of Mormonism. Thousands of years behind us in some of their customs; in others, you would think these people the most forward children of the age. They close no career on a woman in Utah by which she can earn a living.”107 Later, after going on a round of home visits with leaders of the St. George Relief Society, she noted:

A curious difference between the Mormon women and those of an Eastern harem appears in their independence. So many of them seem to have the entire management, not only of their families, but of their households and even outside business affairs, as if they were widows; either because they have houses where their husbands only visit them instead of living day in and day out, or because the husbands are off on Missions and leave the guidance of their business affairs to them.108

As Bessie met more women, it became increasingly difficult for her to think of polygamy in abstract and doctrinal terms. Each individual had her own story. For example, Bessie pitied Eliza B. Young, her hostess in Provo, because her experiences seemed “much more solitary . . . when the evening of her life closed in. No ‘John Anderson’ to be her fireside companion, none of the comfort that even a lonely widow finds in the remembrance of former joys and sorrows shared with one to whom she has been best and nearest.”109 However, Bessie did not pity the “Steerforth” (Pitchforth) wives of Nephi, who lived happily together with their common husband in a single home. These, Bessie wrote, “were the first Mormon women who awakened sympathy in my breast, disassociated from an equally strong feeling of repulsion.”110

She formed a close personal relationship with “Maggie McDiarmid” in St. George. Maggie was willing to admit she had struggled at times in her role as first wife in a plural family. In a sudden outburst, she declared, “I’d have slapped any one’s face twenty years ago that dared to tell me I’d submit to what I have submitted to.” Even so, Maggie insisted she hadn’t “the least fault to find” with her husband and was dedicated to her polygamous marriage.111

Several other themes were skillfully woven into Bessie’s narrative. While attending her first Latter-day Saint church service, she surveyed the Nephi congregation expecting to see “the ‘hopeless, dissatisfied, worn’ expression travelers’ books had bidden me to read” on the women’s faces. Instead, she discovered, they “wore very much the same countenances as the American women of any large rustic and village congregation.” She also found “the irrepressible baby . . . present in greater force than with us, and the element young man wonderfully largely represented. This is always observable in Utah meetings.”112 The services, though less formal than those she was accustomed to, seemed dignified, and the sermons satisfactorily orthodox. Bessie and her young sons especially enjoyed the lively sermons of William Staines. His talk in Nephi “began like a Methodist ‘experience’—became psychological: afterwards touched on the miraculous. A Mormon is never inconvenienced by his story turning on a miracle.”113 In St. George, she heard Erastus Snow deliver “a well reasoned doctrinal sermon, as dry and quite as orthodox as any that I have heard at home.”114 Later, she noted:

The Mormon meetings for spiritual purposes are invaded by the concerns of their daily lives, as much as their daily lives are by their religion. I would not myself like to live either under Roman Catholic or Mormon or Quaker discipline, with either priests or brethren poking their noses into my concerns, but I must confess that it renders the Mormon meetings far more interesting to a stranger who sees their actual doings and intentions “laid before the Lord”, than one of our own Presbyterian or Dutch Reformed or Episcopal services.115

Bessie also developed an appreciation for Mormon prayers and music. The prayers she described as being more specifically concerned with individual persons and events than the “prudent generalities” of Protestant prayers. She added, “I liked this when I became used to it, and could join in with some knowledge of the circumstances of those we prayed for.”116 She wrote, “I do not think they as often say, ‘If it be Thy Will,’ as we do, but simply pray for the blessings they want, expecting that they will be given or withheld, as God knows best.” She also enjoyed the church music in St. George, where the choirmaster, John M. Macfarlane, was an accomplished musician. Of one meeting, Bessie noted, “If there is anything irreverent in the Mormon addresses there is nothing irreverent in their prayers. . . . Nor was there anything irreverent in the hymn that ended our meeting, though there was no organ, and the trained voices of the choir were unpaid. All the congregation joined in the chorus. It went to my heart. I love to see people in earnest.”117

Tom and Bessie met parties of Indians several times and observed them frequently in St. George. Bessie’s distaste for them was explicit, but she admired the more tolerant attitude of her Mormon hosts. Of the Indians she wrote, “They have the appetites of poor relations, and the touchiness of rich ones with money to leave. They come in a swarm; their ponies eat down the golden grain-stacks to their very centres; the Mormon women are tired out baking for the masters, while the squaws hang about the kitchens watching for scraps like unpenned chickens.”118

Tom, however, was very interested in the Indians and took advantage of every occasion to talk with and observe them. In St. George he called Bessie out to observe an arbitration of a dispute between a Paiute man and a Mormon boy over the ownership of a horse. Tom remarked, “It is the first time he ever saw an Indian treated fairly in a Court of Law.”119

Bessie also related a lengthy discussion about the discovery of the gold plates and the translation of the Book of Mormon by Joseph Smith. This occurred in the home of Artemisia Beaman Snow, whose father reputedly assisted Smith as he concealed the Gold Plates. True to her usual approach, Bessie attempted to render the participants’ views in their own words; however, she also inserted her own perceptions:

Mrs. Snow sate knitting a stocking as she talked, like any other homely elderly woman. She certainly seemed to think she had actually gone through the scene she narrated. I know so little of the history of the Mormons that the stories that now followed by the flickering firelight were full of interest to me. I shall write down as much as I can remember, though there must be gaps where allusions were made to things I had never heard of and did not understand enough to remember accurately. The most curious thing was the air of perfect sincerity of all the speakers. I cannot feel doubtful that they believed what they said.120

The mild winter climate of St. George seemed to agree with Tom. Although he needed crutches to walk when they arrived, his strength grew until he was capable of making “a mountain climb of two miles, returning scarcely more fatigued than I was,” and walking without using a cane, something he had been unable to do since the time he was wounded at Harrisonburg.121 Sometime shortly after January 23, he took a turn for the worse, “some dreadful affection—perhaps from cold taken in his wounds. He endured frightful suffering, and lay long at the point of death” before rallying in early February.122

The Mormons’ response to Tom’s illness made a powerful impression on Bessie. She wrote, “I thought myself a pretty good nurse, but I have learned lessons from them.”123 Men were always at hand to lift Tom, “or bathe him with a tender handiness that my feeble strength could not imitate.” A man Bessie referred to as “Elder Johns,” whom she had earlier criticized for devoting too much time and too many resources for the service of others while his own family suffered, now “heaped coals of fire on my head” by his untiring service to Tom. The residents of the three settlements, St. George, Washington, and Santa Clara, assembled in the unfinished tabernacle to offer a special prayer meeting in Tom’s behalf. When she resumed entries in her journal following a hiatus during Tom’s illness, Bessie wrote, “before closing these leaves I write this Memorandum in red ink—

If I had entries in this diary to make again,

they would be written in a kindlier spirit.124

That “kindlier spirit” was evident in the draft of a letter Bessie wrote to her daughter Harriet. Bessie reported that a convalescent Tom had urged her to take the boys for a walk while Brigham Young sat with him. The three family members climbed a little way up the Black Mesa. There they sat while Bessie looked down on the town below and reflected on the good women there who had treated her family so kindly and for whom she could see “no prospect . . . but one of wretchedness.” She concluded:

You will not understand how I have come to pity this people; for you know how hard it was for me to make up my mind to come among them and associate with them, even for the sake of benefiting Fathers health by this climate. I have written to you as a sort of penance for the hard thoughts and contemptuous opinions I have myself instilled into you.

When I came home, I stepped softly to the open door and peeped through. Father was lying in a sound sleep, and a bulky figure that I recognised knelt beside a chair, praying. I stole back and rejoined the children on the porch, and we re-entered the house with sufficient noise to make the watcher aware of our presence. He came out into the parlour to give me the good news that Father had slept almost ever since we left.

Oh, dear H—, I find myself thinking kindly of this man, too!125

To complete her penitential experience, Bessie consented to spend a week with Young’s family in the Lion House (fig. 14) upon the return to Salt Lake City, “a step which I took as a public testimony to the little circle of those to whom my name is known, that my opinion of the Mormon women had so changed during the winter that I was willing to eat salt with them.”126

Epilogue

Tom retained his interest in the welfare of the Latter-day Saints for the remainder of his life. Upon Brigham Young’s death in 1877, Tom again traveled to Utah to reassure himself that the Church was still in capable hands. He also hosted George Q. Cannon at his expanding manorial estate at Kane in 1880.127 In the final moments of his own life in December 1883, Tom instructed Bessie to “send the sweetest message you can make up to my Mormon friends—to all, my dear Mormon friends.”128

The warm feelings toward the Mormons with which Bessie left St. George in 1873 cooled somewhat in subsequent years. She lived to see the Church leaders announce the 1890 Manifesto ending plural marriage and the 1896 achievement of Utah statehood, a goal toward which her husband had tirelessly worked. When she learned that a travel writer was planning to publish a book in which he would renew the claim that Thomas L. Kane had secretly been a Mormon, she was stirred to a vigorous defense of her late husband’s reputation in which she did not spare her Mormon friends. “General Kane was a highly educated man,” she wrote. “It would have been as impossible for him as for yourself to accept the teachings or authority of the Book of Mormon or the Book of Doctrine and Covenants.” His devotion to the Mormons arose solely from his recognition that he “owed his life to the tender care and nursing that he received from the Mormons” in 1846. “He was particularly grateful to Brigham Young; and throughout the rest of his life he showed his gratitude to the Mormons and his pity for that people at the cost of obloquy cast upon him by his dearest friends, and at the risk of his life. But gratitude and pity were his sole incentives to all he did.” She continued, “As he saw the Mormon people, he felt that many of their detractors and enemies could not afford to throw a stone at them, and he believed that their theory was better than the practice of many of their enemies.” Then she wrote and subsequently cancelled a more damning judgment: “It is of course true that their theory is as much below true Christianity as the practice of bad Mormons, or perhaps one may say of any Mormons is below that of good, ordinary citizens.”129

Pandemonium or Arcadia?

About the author(s)

Edward A. Geary earned his PhD in English literature from Stanford University. At Brigham Young University, he taught in the English Department, directed the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies, worked as editor in chief of BYU Studies, participated in London study abroad programs, and served as an associate dean in the College of Humanities and as chair of the English Department.

Notes

1. Elizabeth Wood Kane, Twelve Mormon Homes Visited in Succession on a Journey through Utah to Arizona, ed. Everett L. Cooley (Philadelphia: William Wood, 1874; reprint, Salt Lake City: Tanner Trust Fund, University of Utah Library, 1974); Elizabeth Wood Kane, A Gentile Account of Life in Utah’s Dixie, 1872–73, ed. Norman R. Bowen (Salt Lake City: Tanner Trust Fund, University of Utah Library, 1995).

2. “Autobiography of John K. Kane,” typescript, 1–8, Thomas L. Kane and Elizabeth W. Kane Collection, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, (hereafter cited as Perry Special Collections). References to family connections occur in John K. Kane’s autobiography as well as in numerous family letters in the Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections. See also Elizabeth D. Kane, “Memorandum of E. D. Kane relating to Gen Washington’s occupation of John Kane’s house as Headquarters in 1778,” Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

3. Mark Metzler Sawin, “Heroic Ambition: The Early Life of Dr. Elisha Kent Kane,” American Philosophical Society Library Bulletin 2 (Fall 2002): 2, http://www.amphilsoc.org/bulletin/2002/kane.htm.

4. He served as a federal commissioner to settle war claims with France, as Philadelphia city solicitor, as attorney general of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and from 1846 to the end of his life in 1858 as United States district judge. Sawin, “Heroic Ambition,” 4.

5. Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 227–29.

6. Sawin, “Heroic Ambition,” 5.

7. Sawin, “Heroic Ambition,” 3–4. During the Jackson administration, Kane reportedly served occasionally as a speechwriter and as an adviser to the president.

8. John K. Kane to Elisha Kent Kane, June 14, 1844, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

9. Sawin, “Heroic Ambition,” 4, 5; Matthew J. Grow, “Liberty to the Downtrodden”: Thomas L. Kane, Romantic Reformer (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009), 6, 7, 19, 21.

10. Thomas L. Kane to John K. Kane, July 28, 1840, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

11. John K. Kane to Thomas L. Kane, July 1, 1839, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

12. See Grow, “Liberty to the Downtrodden,” 22–23. There is no mention in the letters he wrote from Paris of any kind of personal association with Comté, beyond one brief meeting. BYU’s Kane Collection includes a later letter from Comté that bears a notation in Tom’s handwriting as coming from one of his “two best friends.” However, there is nothing of a personal nature in the letter itself. It is a perfunctory letter of thanks for a contribution Tom had sent anonymously to the French philosopher. Auguste Comté to Thomas L. Kane, October 27, 1851, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

13. Thomas L. Kane to Elisha Kent Kane, June 8, 1845, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

14. “Elizabeth Dennistoun Kane, the Mother of Kane,” Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

15. William Wood, Autobiography of William Wood, 2 vols., ed. Elizabeth Wood Kane (New York: J. S. Babcock, 1895), 1:119.

16. William Wood to Thomas L. Kane, October 2, 1840, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

17. Thomas L. Kane to John K. Kane and Jane D. Leiper Kane, October 3, 1840, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

18. Thomas L. Kane to John K. Kane and Jane D. L. Kane, October 28, 1843, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections; Thomas L. Kane to John K. Kane and Jane D. L. Kane, March 28, 1844, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

19. John K. Kane to Thomas L. Kane, January 3, 1846, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

20. Albert L. Zobell Jr., Sentinel in the East: A Biography of Thomas L. Kane (Salt Lake City: Nicolas G. Morgan, 1965), 2–3. For more on Jesse C. Little, see Richard Bennett’s essay herein.

21. Thomas L. Kane to Elisha K. Kane, May 16–17, 1846, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, Penn.; quoted in David L. Bigler and Will Bagley, Army of Israel: Mormon Battalion Narratives (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2000), 55–56. In letters to his brother Elisha, Tom reported that with “a little tact and patience and a little maneouvring” in Philadelphia he had gained the trust of Jesse C. Little, who had provided him with letters to Church leaders. Tom envisioned the advance party of Mormons carrying “to California the first news of War with Mexico.” With California falling into U.S. control, “at one time or other a government representative may be wanting. Who so fit for one as I?—above all if on the journey I shall have ingratiated myself with the disaffected Mormon army before it descends upon the plains. I could carry my commission in my money belt, and according to the promptings of occasion, be or be not the first U.S. Governor of the new territory of California.” Thomas L. Kane to Elisha K. Kane, May 16–17, 1846, American Philosophical Society.

22. Sawin, “Heroic Ambition,” 26.

23. Thomas L. Kane to George Bancroft, July 11, 1846, original in Bancroft Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Mass., typescript copy in Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

24. Colonel Kearney to Thomas L. Kane, June 25, 1846, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections; W. Gilpin to Thomas L. Kane, June 29, 1846, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

25. Thomas L. Kane to “My Own Dear Father and Mother,” July 18–22, 1846, The Papers of Thomas Leiper Kane, Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City (original in American Philosophical Society library); quoted in Bigler and Bagley, Army of Israel, 58.

26. Thomas L. Kane to Elisha Kent Kane, May 29, 1846, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

27. Thomas L. Kane to Elizabeth D. Wood, May 19, 1852, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

28. Thomas L. Kane to “My Own Dear Father and Mother,” July 18–22, 1846, The Papers of Thomas Leiper Kane, Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, quoted in Bigler and Bagley, Army of Israel, 58, 60, 61.

29. Thomas L. Kane to “My dear friends, all of you,” July 11, 1850, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, quoted in Leonard J. Arrington, “‘In Honorable Remembrance’: Thomas L. Kane’s Services to the Mormons,” BYU Studies 21, no. 4 (1981): 392.

30. For a longer discussion of this topic see William McKinnon’s essay herein.

31. Thomas L. Kane alludes to Book of Mormon teachings on the Native American Indians in The Mormons, 70; he also quotes what were then sections 109 and 110 of the Doctrine and Covenants in the Postscript to the Second Edition, 88, 89. There is also a letter to Brigham Young in which Kane describes the signet rings he has had made for Church leaders from some California gold they had sent to him. The rings bore symbols from the Book of Mormon. Thomas L. Kane to Brigham Young, February 19, 1851, quoted in Zobell, Sentinel in the East, 50–52.

32. Elizabeth D. Kane, 1858–1860 Journal, July 11, 1859, typescript, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

33. Kane, Gentile Account, 164.

34. Grow, “Liberty to the Downtrodden,” 278.

35. Thomas L. Kane to Elisha K. Kane, June 8, 1845, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

36. Grow, “Liberty to the Downtrodden,” 278.

37. Thomas L. Kane to Brigham Young, December 2, 1846, quoted in Zobell, Sentinel in the East, 29–30.

38. Thomas L. Kane, The Mormons: A Discourse Delivered before the Historical Society of Pennsylvania: March 26, 1850 (Philadelphia: King and Baird, 1850). For more on this lecture, see Richard Bennett’s essay herein.

39. Kane, The Mormons, 3.

40. Kane, The Mormons, 4.

41. Kane, The Mormons, 10.

42. Kane, The Mormons, 25–26.

43. Kane, The Mormons, 26, 27.

44. Kane, The Mormons, 27.

45. Kane, The Mormons, 34.

46. Kane, The Mormons, 47.

47. Kane, The Mormons, 29, 28.

48. Kane, The Mormons, 85.

49. Kane, The Mormons, 88 n. The “Postscript to the Second Edition” is reproduced in full as an appendix to Zobell, Sentinel in the East.

50. William Wood to Thomas L. Kane, April 25, 1851, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

51. William Wood to Thomas L. Kane, June 14, 1851, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

52. See Gene A. Sessions, Mormon Thunder: A Documentary History of Jedediah Morgan Grant (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982); Grow, “Liberty to the Downtrodden,” 88.

53. Thomas L. Kane, Journal/Notebook, November 11, 1851–September 27, 1852, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

54. Thomas L. Kane to John M. Bernhisel, December 29, 1851, draft, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

55. Thomas L. Kane to William Wood, May 21, 1852, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

56. Thomas L. Kane to Brigham Young, October 17, 1852, quoted in Zobell, Sentinel in the East, 71–72.

57. Remarks of Dr. John M. Bernhisel to C. VanDyke, quoted in Zobell, Sentinel in the East, 104.

58. Elizabeth D. Kane to Rev. Dr. Buckley, March 6, 1906, draft, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

59. “Elizabeth Dennistoun Kane, the Mother of Kane,” Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

60. “Elizabeth Dennistoun Kane, the Mother of Kane,” Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

61. Elizabeth D. Wood to Thomas L. Kane, July 18, 1852, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

62. Wood to Kane, July 18, 1852.

63. William Wood to Thomas L. Kane, March 18, 1852, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

64. Elizabeth D. Wood to Thomas L. Kane, September 19, 1852, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

65. Elizabeth D. Wood to Thomas L. Kane, August 8, 1852, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

66. Elizabeth D. Wood to Thomas L. Kane, August 8, September 2, 1852, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

67. Thomas L. Kane to Elizabeth D. Wood, August 6, 1852, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

68. Elizabeth D. Wood to Thomas L. Kane, September 23, 1852, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

69. Elizabeth D. Wood to Thomas L. Kane, September 30, 1852, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

70. William Wood to Thomas L. Kane, November 25, 1852, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

71. Grow, “Liberty to the Downtrodden,” 133.

72. See Darcee D. Barnes, “A Biographical Study of Elizabeth D. Kane” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 2002).

73. Grow, “Liberty to the Downtrodden,” 155, 160.

74. Elizabeth D. Kane, 1857–58 Journal, February 2, 1858, typescript, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

75. Kane, 1857–58 Journal, June 20, 1858, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

76. Kane, 1857–58 Journal, December 26, 1857, December 28, 1857, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

77. Kane, 1857–58 Journal, June 20, 1858, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

78. Thomas L. Kane to [President Buchanan?], March 4, 1858, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

79. Thomas L. Kane to [President Buchanan?], c. March 15, 1858, Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.

80. Thomas L. Kane to John K. Kane, n.d., Kane Collection, Perry Special Collections.