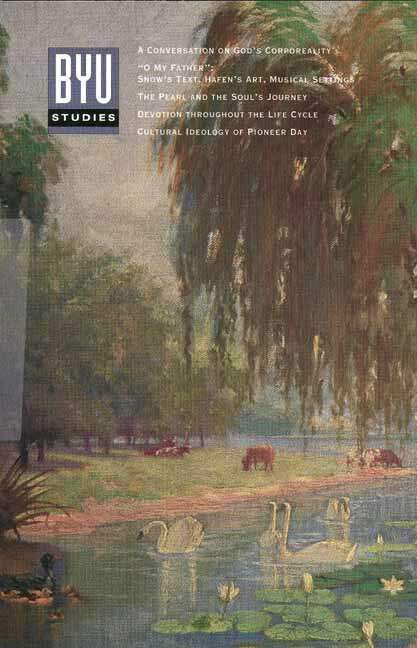

Testimony in Art

John Hafen's Illustrations for “O My Father”

Article

-

By

Dawn Pheysey,

Contents

The year 1890 was the beginning of John Hafen’s artistic alliance with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, an association that would eventually culminate in his illustrations of the well-known Mormon hymn “O My Father.” Believing that art could be a powerful motivating factor in the advancement of religious ideas, Utah artists John Hafen and Lorus Pratt approached George Q. Cannon, first counselor in the First Presidency of the Church, requesting financial support to study art in France. In return, the artists would use their improved skills to paint murals for the temples.

As a result of this communication, Hafen and his fellow artists John B. Fairbanks, Lorus Pratt, and later, Edwin Evans were set apart as art missionaries to receive training in one of Europe’s finest art schools, the Julian Academy in Paris. Hafen’s desire to apply “[his] talent to the service of God and the beautifying of Zion”1 motivated him in Paris and throughout his life. Determined to learn all that he could in the time allotted him to study in France, he wrote, “I hope above all things God will give me devine assistance so I can make unusual progress.”2

Instructors at the Julian Academy emphasized precise rendering, thereby providing the Utah artists with a strong foundation in drawing. The Utahns were equally inspired by the plein-air painters of the Barbizon school, whose idyllic paintings recorded unedited blends of man, animals, and landscape. The Utah artists also adapted the expressive use of color, the visual effects of light, and the broken brushstrokes of the impressionists to achieve a fresh spontaneity in their paintings. Consequently, they spent a substantial time sketching outdoors. In a letter to his wife, Hafen wrote, “I feel like keeping my out of door acquaintance with nature on a par with my acquaintance of the human figure inasmuch as both are studies and likewise cultivate drawing abilities.”3 Integrating the various influences of the Paris art experience, Hafen developed a style that was uniquely his own. The combination of these artistic conventions would be seen in his future landscape and portrait paintings, as well as the “O My Father” illustrations.

In 1891, a year after his return from Paris, Hafen and other Utah artists quickly executed the mural for the garden room in the Salt Lake Temple, thus fulfilling the major purpose of the art mission. The contribution of the Utah art missionaries was also seen in the strengthening of the state’s art organizations and in the enhancement of art instruction.

In the years that followed, Hafen was plagued by financial difficulties as he struggled for recognition as a viable artist. With his artwork finding few sales in his home state of Utah, he found it necessary to travel to Washington, California, the East Coast, and later, the Midwest to pursue his artistic career. Sustained by his faith in God, Hafen was determined to paint. He longed to use his God-given talents to provide for his large family and to further the message of the gospel, but fame and financial stability eluded him throughout his life. While he was living in Nashville, Indiana, he received a letter from his wife, Thora, expressing the sentiment felt by both of them: “The reason you are not permitted to do for your family as you would like, is that the Lord wants to teach us all the lesson of faith. He has His own way of doing it, and it sometimes seems hard to us.”4

In order to support his growing family adequately, he approached the Church for financial assistance several times beginning in 1901. In exchange, he completed a number of paintings for the Church, including the familiar Girl among the Hollyhocks and a series of portraits of the General Authorities.

In the spring of 1908, Hafen again left his family behind and went east to paint and market his work. While working in Chicago, he was invited to exhibit his paintings in a one-man show at Marshall Field’s Gallery. He received much praise and recognition, but, unfortunately, art sales were few and brought in only enough money to pay his expenses. Although monetary circumstances became dire, Hafen retained his sense of humor and was later to write, “I believe some times the Lord would kill a man or make him awful sick and full of trouble if he intended to buy some of my pictures.”5 As he was always on the brink of financial despair, the trial of his faith continued.

During this period, Hafen met with the president of the Eastern States Mission, Ben E. Rich, and they discussed a plan to illustrate and publish “O My Father,” the great Latter-day Saint poem written by Eliza R. Snow. This was not an official Church commission, but merely a suggestion from President Rich as a means of teaching the gospel.6 A short time later, German E. Ellsworth, president of the Northern States Mission, also became involved in the project. He led Hafen to believe that thousands of the illustrated booklets would be sold and the venture would be profitable for him, providing him with a source of income. Both mission presidents were to finance the project and put it on the market, taking only a small portion of the profit for their trouble in getting it published. All the rest of the proceeds were to go to the artist. President Ellsworth thought he could sell five or six thousand before Christmas 1908 if Hafen could finish them.7

Although Hafen was financially desperate, his profound faith was the main motivation behind the paintings of the “O My Father” series. The opportunity to share gospel principles through this medium prompted Hafen to write, “I have thought about it almost constantly ever since brother Rich sugested it to me. I am impressed with the means that the pictorial art might be of spreading the grand truths which are in that poem.”8

In a subsequent letter to President Rich, Hafen expressed his great interest and enthusiasm for the project. He indicated that he had spent considerable time reading and studying the poem before making the proposal for the illustrations. Outlining his initial ideas, he wrote:

First the poem impresses me as a prayer. Hence my imagination opens up the group of pictures with a figure in the attitude of prayer. Then succeeding pictures deal with visionary subjects chiefly. In a general way I am also inclined to think the commencement of the inspired principles set forth or suggested in the poem, begin in childhood. For instance, in the second and third theme, is childhood. In the fourth, fifth, and sixth themes, youth and early manhood; and more matured thoughts and reflections contained in the 4th verse which I have made into two themes, for the meridian or afternoon of life. The last verse represents ripe old age, when we are about ready to meet our Maker again.

I believe that the 1st and 2nd themes, also the 11th and 12th, might be made into one each, making in all 10 themes instead of 12.9

Feeling the magnitude and potential influence of this commission, Hafen asked President Rich for his sympathy, faith, and prayers to help him in this cause. In a meeting, Hafen and President Ellsworth determined that the purpose of the illustrations should be to “make plain the meaning of the song to common people, so they could better comprehend the meaning of the grand principles set forth in the verses.”10

That summer Hafen went to Indiana at the invitation of Adolph Shulz, a friend from his Paris days. Under the direction of Shulz, Hafen and a group of Chicago artists established an art colony in rural Brown County.11 The quaint, wooded landscape of Nashville provided the artists with undefiled views of nature for their paintings. In this peaceful setting, Hafen worked on the illustrations for the “O My Father” series.

As the work progressed, Hafen felt that the Lord was “dirrecting and opening up the way for this work and therefore there must be something in it.”12 By using family members and local Church leaders as models,13 he gave added emphasis to the family relationships conveyed in the poem.

By December 1908, he had completed four of the illustrations and said he expected to have the remaining paintings done early in January 1909. A few months after the paintings were completed, Hafen received a postcard from President Ellsworth saying there was a delay in producing the booklet and he would do what he could to clear up the problem.14 Church authorities were concerned about the distribution of the illustrated poem. In response, Ellsworth traveled to Salt Lake City and spoke with the First Presidency, arguing “away the objections and got the authorities’ consent to go ahead with the sale of the booklets, President [Joseph F.] Smith offering to buy the first one.”15 Hafen sent 475 booklets to Thora to sell, assuring her that the “illustrations [were] done just right, they were not only done in the best possible way but that they were done under the inspiration of the Lord.”16

It is unclear what happened regarding the “O My Father” booklet in the next two months, but some difficulty or misunderstanding prompted Hafen to write to the Church authorities. At the root of the problem appeared to be concern about publishing the booklet under the name of the Church and the complications that would follow from such an action. From all indications, the Church authorities gave permission for the booklet to be sold privately but denied approval for distribution by the missionaries as such an action would imply endorsement.

Frustrated by the reticence of the First Presidency to endorse the “O My Father” booklet and interpreting their reluctance as criticism of his artistic interpretation of the poem, Hafen wrote a lengthy letter to them expressing his disappointment. Because he believed they did not comprehend the specific mission of art and the rationale for his illustrations, Hafen was anxious for them to understand why he had illustrated the poem as he had. In defense of his approach, he expounded on the relationship between his art and his deeply held beliefs. For Hafen the mission of art was not

to ape or imitate anything, but primarily to interpret or reveal beauty in line and color. It is also within the province of an artist’s calling to express beauty in philosophy and principle so far as it lies in the power of the pigments that he uses. . . . I am . . . convinced that anything in the eternal world is not ilustratable by reason of materialistic limitations, and also by reason that what we cannot see we canot interpret by form language. So far as this view goes I am in perfect harmony with those who believe that the poem in question is not ilustratable. But, I do believe, for the best of reasons, that the philosophy and the principles involved in the poem “O My Father” are ilustratable and afford good material for artistic themes. This is as far as I dared to venture in dealing with the material of this poem. This is one reason why I used common-place subjects. Another reason is that there is already too much speculation and mystery in the world regarding conditions in the eternal world.17

The doctrine espoused in the “O My Father” hymn was at the core of Hafen’s religious convictions. He saw the celestial family relationship as a progressive continuation of his earthly family associations:

I well remember how a certain minister at a religious convention in Salt Lake City ridiculed the mormon idea of fatherhood and motherhood as expressed in their hym and how degenerating it was &c. I realy have rejoiced in this privilege of . . . ilustrating and therby asserting the reality and tangibility of our eternal existance. I have felt, all along, that I could not be too realistic in the treatment of this matter.

To me heaven, God, eternity, is a living materialistic reality. I have business with my Heavenly Father every day of my life; I love Him; I am well acquainted with Him. I also have friends in the other world and brothers and sisters; also a father and mother. . . . I expect to meet them all and have a joyful time in talking over experiences. These feelings have had much to do with the manner in which I have ilustrated this beautiful consistant and truthful poem.18

Believing that the First Presidency’s objections were based on his interpretations of the poem’s doctrine, Hafen questioned their supposed reactions to the illustrations. He saw these earthly manifestations of divine love as a concept to which the humblest of people could relate. It was his intention that all who saw the illustrations would be able to identify with the truths contained therein.

I will ask [are] there any principles or features in the eight ilustrations which take from or belittle any truth or philosophy in the poem? Is the fact, as ilustrated for instance, of a father having a child by his side or a child having a father as a companion in walking out in nature? Is there anything but a good and an elevating thought in this? How about the mother clasping her child to her bosom in love, or an innocent babe sitting on the ground? What could there be in the sentiment of these subjects that would detract a single point from the grand poetic flow in the immaginative element in the poem? Brethren I have listened to this song when picture after picture was exposed to view as the words of the song flowed from the lips of the singers and I testify that these pictures added very much to the grandure of the sentiments in the poem. . . .

In conclusion I wish to bear my testamony that I have sought the Lord for help and inspiration in composing and executing those pictures, and that this trust has not been in vain. I feel that good will result from the spread of these ilustrations with accompaning poem: and that even souls will be brought to a knowledge of the true and living God through their instrumentality.19

Although Hafen believed that the First Presidency was dissatisfied with his artistic treatment of the poem, they, in actuality, were only concerned about the ramifications of Church endorsement. In a letter, the First Presidency praised the pictures, “especially some of them which [they] thought really beautiful.” They explained that if the business venture had been carried out as planned,

the sale of the work would naturally carry with it the idea, that this was being done on Church authority, and the agents would naturally emphasize this idea in their endeavors to make sales; and if this were done, it could only be a question of time when the Church would be called upon to explain its position in relation to it; . . . and it was to avoid this that we withheld our consent to their publishing it.20

They had no objection, however, to someone other than an officer of the Church producing and selling the work. Consequently, friends and family members were enlisted to sell the “Illustrated Poem,”21 thus helping to defray the costs of publication. Originally, the booklets were to sell for about one dollar each,22 but later the price was reduced to fifty cents. Hafen made twenty cents commission on each booklet sold.23

Hafen’s lifetime of experiences equipped him with the wisdom necessary to illustrate the gospel truths from this prophetic poem. Because of the deep faith that sustained him through difficult trials, he was able to portray not only the hope, but also the surety of a heavenly home. At Hafen’s death, B. H. Roberts gave the following tribute:

[His life] was successful and I cannot help but believe it was all the more successful because it was sorrowful. This struggle of his had something to do with the success in his calling. . . . When God will give great poems to the world, he takes some great soul and gives it great sorrow and out of that sorrow the poet sings. It is as true of artists as of poets and some of that has come into the life of John Hafen.24

The eight illustrations (two watercolors and six oils) and accompanying poem not only cultivated the love of art and poetry, but also fulfilled the booklet’s function to teach gospel truths. Each painting in the series allows us to see and understand the eternal plan of salvation. At the same time, it gives us a glimpse into the soul of John Hafen.

“O My Father” Illustrations

O My Father, Thou that dwellest In the high and glorious place When shall I regain Thy presence, and again behold Thy face?25

Oil on paper, 1908. 18⅝” × 10¾”, sight size. (See plate 1.)

In this first illustration, Hafen depicts a young man26 kneeling in prayer on a jutting rock formation, addressing his Heavenly Father in all sincerity and humility. His lone figure against a cold, bleak landscape gives emphasis to the man’s desire to return to the heavenly realm of peace, safety, and love. Hafen knew what it meant to be alone in an impersonal world. Forced by economic circumstances to be away from his family for prolonged periods of time, he, too, felt an intense longing for home, to be reunited with his wife and children. While in Indiana, Hafen wrote to Thora expressing the same heartrending sentiments that he had expressed so many times before: “I am desperately wanting to have you with me. I need your encouraging counsel and love by me continuely. I want to enjoy my children that God has given me.”27 Hafen’s artistic interpretation of this segment of the poem reflects the yearning for familial companionship that enabled him to paint with empathetic conviction.

In Thy holy habitation Did my spirit once reside; In my first primeval childhood, Was I nurtured near Thy side.

Oil on paper, 1909. 19⅛” × 10¾”, sight size. (See plate 2.)

The first verse of “O My Father” culminates in a powerful commentary on the doctrine of premortality. Although the poem refers to habitation with our Heavenly Father, Hafen chose an earthly father and his daughter to represent that celestial family relationship. The young girl holds her father’s hand in both of hers as they pause along a path in a lush, green setting. Soon she must leave the father’s presence and his kind and gentle tutoring. The trust with which she looks at him and his respondent tenderness is a manifestation of that heavenly relationship we have with our Father in Heaven and He with us. Even the unbuttoned jacket and the openness created by the angle of the father’s feet suggest that Heavenly Father is approachable, open to our inquiries and petitions.

With a tropical palm tree incorporated into a landscape of pine trees and colorful wildflowers, the scenery is reminiscent of Hafen’s Garden of Eden study for the Salt Lake City Temple garden room. He infused his paintings with the essence of nature and encouraged his viewers to cease looking “for mechanical effect or minute finish, . . . or aped imitation of things, but look for smell, for soul, for feeling, for the beautiful in line and color.”28 Here the visual sensations of nature elevate our thoughts and sentiments to the divine principle of the premortality taught in “O My Father.” In contrast to the cold, stark landscape of the previous painting, warmth, light, and color infiltrate this work, creating an ambiance of affection and familiarity between the two figures. Using his daughter Rachel and his friend George Edward Anderson, the photographer, as models, Hafen achieved an expression of parental love, underscoring it with the radiant glow of the landscape.

For a wise and glorious purpose Thou hast placed me here on earth, And withheld the recollection Of my former friends and birth.

Oil on paper, 1908. 18⅝” × 10¾”, sight size. (See plate 3.)

The doctrine of premortality in the first verse of the poem is followed by the principle of our earthly probation. An angelic image of a young child with her finger in her mouth, dressed in white and sitting on the grass, speaks of a baby’s total innocence. Having forgotten the premortal existence and unaware of the joys and challenges that lie ahead, the young baby begins her mortal journey. Hafen uses artistic conventions to define the passage from a pre-earth life to a temporal experience. The hazy edge on the left suggests the blurred remembrance of a former life. The background progresses across the painting from light to shadow to dark signifying a transition from premortality to mortality. The light and dark contrast implies the vast difference between the two realms—one filled with light and truth, the other with opposition and uncertainties. With the memory of an earlier life suspended, each individual is left to choose between the forces of good and evil in fulfilling his or her potential. The artist reinforces this concept by the effective use of contrasting values.

During his early days in Paris, Hafen affirmed his understanding of humanity’s responsibility to progress and learn while in this earthly state. “I believe,” he wrote, “a person should be dilligent in improving his faculties all his life time; for what else is this probation except a link in the great eternal link of progression. Thus it is; no matter in what possition we are in in life, if we contemplate upon the plan of salvation we receive encouragement and assurances.”29 As emphasis to his words, Hafen approached life with an enthusiastic desire to pursue and amplify his talents, confident that God would assist him in all his worthwhile endeavors.

Hafen was also very much aware that life would have its trials and disappointments. Believing there was a purpose behind all mortal difficulties, the Hafens put their trust in the Lord:

The trying adversity which has beset our path and troubled and tried us so severely all our married life . . . has undoubtedly been the making of us. This condition has been the greatest blessing . . . that God our eternal Father could have bestowed upon us. . . . [M]y heart swelled with gratitude to my Heavenly Father for His mindfullness of us: for placing us in sircumstances where we would be led to develope faith in our Heavenly Father and in the gospel.30

In spite of discouraging circumstances, Hafen never doubted his value as an artist, nor did he doubt that God would provide a way for him to achieve success.

According to family members, the baby in the painting is Anna Larson, Hafen’s granddaughter. He probably painted her from one of the two photographs he carried of her in his pocketbook.31

Yet oft-times a secret something Whispered, “You’re a stranger here”; And I felt that I had wandered from a more exalted sphere.

Oil on paper, 1908. 19½” × 11 15/16″, sight size. (See plate 4.)

Hafen places a young woman32 in the intimate setting of an aspen grove. In this autumn scene, a blanket of fallen leaves covers the ground. The path, originating beyond the borders of the painting, pulls the viewer from one sphere into another and into that wooded landscape. The subtle color scheme heightens the contemplative mood of the scene.

Utah’s mountain landscapes with their quaking-aspen groves provided Hafen with the material he needed for painting. He rejoiced at the “ever-varying woodland paths . . . darting through dense forests”33 that filled him with exhilaration.

To Hafen, nature was a spiritual manifestation of God’s love. In a letter to a friend, he wrote, “We could do without the flowers in the fields and mountains or by the wayside. We could do without the various colors which adorn the face of nature; but an allwise and generous Creator has placed them there for the welfare of his children.”34 In this letter, Hafen’s description of nature’s changing moods takes on a human quality, paralleling life’s “storms and sunshines” while in this probationary state.

In his association with God’s creations, Hafen discovered sacred truths and sentiments. This painting’s mood-filled landscape conveys the delicate feelings of one who is in but not of the world. Writing on the subject of nature, he quoted: “It stands for a natural expression of what is outside and beyond ourselves, and . . . it helps us to look up and out, to see beauty and charm in everything about us; to broaden our mental horizon, to elevate our feelings, to double our capacity for enjoyment, to feel the poetry and harmony of life.”35

I had learned to call Thee Father Thro’ Thy Spirit from on high; But until the KEY of KNOWLEDGE was restored, I knew not why.

Oil on paper, 1909. 19⅛” × 10¾”, sight size. (See plate 5.)

The only immortal being illustrated in the poem is the angel Moroni, who here stands slightly above the ground with his right hand raised. He is dressed in an open white robe surrounded by an emanating light. Joseph Smith leans forward in eager anticipation as he listens to the words of the heavenly being. To his left is the open stone box containing the gold plates, the Urim and Thummim, and the breastplate. A large stone, thick and rounded in the middle, partially covers the box. Depicting the moment when the angel Moroni revealed the box and its contents to Joseph Smith, Hafen represented the restoration of gospel knowledge.

Hafen himself fervently embraced the restored gospel. He appreciated “beyond expression the daily reading from the Testament and Book of Mormon.” He wrote, “The Lord has given these writings for a purpose and He wants us to use them and make ourselves acquainted with them.”36

It is likely that Hafen’s son Virgil was the model for Joseph Smith. During young manhood, Virgil struggled with his testimony. It seems probable that Hafen chose his son as the model in the hope that he would experience an affinity with the young prophet and thus strengthen his own testimony. At the time this illustration was done, Virgil lived with his father in Indiana. Later he attended the John Herron Art Institute in Indianapolis, where he studied painting and drawing.

In the heav’ns are parents single? No; the tho’t makes reason stare! Truth is reason, truth eternal, Tells me I’ve a MOTHER there.

Watercolor, 1908. 18⅝” × 10¾”, sight size. (See plate 6.)

This monochromatic painting of two figures against the sky is a tender and sensitive portrayal of a mother’s love. The mother encircles the girl in the comfort of her arms and rests her head on that of her daughter. Again Hafen uses a mortal mother to represent our Heavenly Mother. What more appropriate models for Hafen to use than those of his beloved wife, Thora, and their daughter Delia.

The painting prophetically defines the real-life relationship between this mother and daughter, as described by Hafen in a letter several months after the painting was completed. In that letter, Hafen praises the love that Thora has for her children and offers loving counsel to Delia:

Love mama confide and trust in her; she is full of love for you and wishes to do all she can for you just the same as when she cradled you in her arms and hugged you to her bosom and showered those loving kisses upon your sweet baby face. A mother’s love never dies, or even diminishes! There is no friend or protector on earth that can possibly excell a mother’s love. . . . Remember darling daughter that a mother will stand by her child when all the world will scorn it.37

When I leave this frail existence, When I lay this mortal by, Father, Mother, may I meet you In your royal courts on high?

Oil on paper, 1909. 19¼” × 11 3/16″, sight size. (See plate 7.)

In this painting, the waning hours in the sunset of life are emphasized by a soft, hazy glow on the horizon that obscures all surrounding details. The old man’s profile is highlighted by the setting sun as he turns toward the light. Influenced by his previous association with the Barbizon school of painters, Hafen uses a subtle color scheme with dominant halftones to produce a strong pictorial effect.

Here, as in other illustrations of the series, the use of a path signifies the road we all must travel as we make that sacred pilgrimage back to our heavenly home. Perhaps Hafen saw something of himself in this elderly gentleman with head bent and shoulders stooped with age. Although he was only in his early fifties at this time, the difficulty of his life’s journey had aged him but also endowed him with the wisdom, maturity, and experience of an older man. Writing to a friend in Salt Lake City, Hafen said:

Now that my hairs have turned white with time and a diligent, long, hard fight for what there is good in my grand profession, I can take a glance over the field of the world’s accomplishment, at least from a high eminence, and can see better now than ever before what the Lord has and is doing for me, in reward for my trust and faith in him.38

Then, at length, When I’ve completed All you sent me forth to do, With your mutual approbation Let me come and dwell with you.

Watercolor, 1909. 18¼” × 9 7/16″, sight size. (See plate 8.)

Again we see the aged gentleman from the previous painting—who was modeled after the patriarch John Lowry. The soft, sienna tone of the painting suggests another realm into which this weary traveler has journeyed. Hafen himself had so few earthly possessions, one wonders what he envisioned in the lumpy knapsack hoisted over the old man’s shoulders. The open gate and pathway leading to the multispired mansion seem to welcome him back to his celestial abode.

Conclusion

One year after the completion of these eight illustrations, John Hafen himself returned to his heavenly home. On the verge of financial success, he died of pneumonia June 3, 1910, only two weeks after his family had joined him in Indianapolis. Alice Merrill Horne beautifully and succinctly captured the essence of John Hafen’s life:

Though Hafen’s beginnings were humble; though others have commenced the ascent of the roadway of fame with seemingly larger assets; though he has groped on a lonely way; though obstacles were continuously thrust before him; though poverty has struggled to defeat him, yet he has believed in his gift. He has never loosened the grip of his stubborn hold, for at each crisis through which he passed, his consciousness of his soul’s inspiration has overwhelmed the power of destructive agents about him; therefore he has won the battles.39

He was tenacious in the conviction that his calling in life was to be an artist and was determined “to be instrumental in exalting the beautiful art to a high position among the people of God so that the world may know what power there is in the gospel.”40 As a result, he attained the ultimate success as one who brought “great honor to the church and people of God.”41

The “O My Father” paintings represent one of the finest unions of poetry and art ever produced. These were not merely illustrations of a poem; they were sincere portrayals of truths that the artist embraced. Hafen believed that “good art is . . . much dependent on truth.” He wrote, “A man or woman who has wrong ideas of his or her . . . religion, of God, and of duty, cannot become a great artist, be they ever so gifted.”42 This illustrated narrative of fundamental Latter-day Saint concepts sprang from his very soul and fulfilled a longing for visual expression of his beliefs. As an art student in Paris, he wrote, “All the noble accomplishments in the arts and sciences only implant the truth deeper in the human heart.”43

It has long been a common practice to promulgate religious beliefs through the visual arts. This means of representation was revitalized by early Latter-day Saint artists who painted scenes from Church history and emphasized gospel tenets as testimonials to their faith. As one of early Utah’s greatest artists, John Hafen combined art and illustration in a powerful fusion of vision and spirit to fortify the gospel principles he espoused.

About the author(s)

Dawn Pheysey is Curator of Prints and Drawings and Manager of the Print Study Room, Museum of Art, Brigham Young University.

The author expresses appreciation to Carol Hafen Jones, granddaughter of John Hafen, for sharing not only her Hafen family files, but also her personal knowledge and insight. Other members of the Hafen family, Joseph Hafen and Norma Hafen Henrie, also contributed valuable information about the “O My Father” series. Finally, she thanks Robert Davis, Senior Curator at the Museum of Church History and Art, for his review and suggestions.

Notes

1. John Hafen to George Q. Cannon, Springville, Utah, March 25, 1890. Unless otherwise indicated, all letters quoted are in the John Hafen correspondence file, Special Collections and Manuscripts, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

2. John Hafen to Thora Hafen, Paris, France, July 25, 1890; letter started July 22, 1890, in London, England.

3. John Hafen to Thora Hafen, Paris, France, August 15, 1890, quoted in Linda Jones Gibbs, Harvesting the Light: The Paris Art Mission and Beginnings of Utah Impressionism (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1987), 25.

4. Thora Hafen to John Hafen, Provo, Utah, October 25, 1908.

5. John Hafen to Thora Hafen, Indianapolis, Indiana, November 10, 1909.

6. John Hafen to Thora Hafen, Chicago, Illinois, July 16, 1908.

7. John Hafen to Thora Hafen, Nashville, Indiana, July 30, 1908.

8. John Hafen to Thora Hafen, Chicago, Illinois, June 24, 1908.

9. John Hafen to President Ben E. Rich, Chicago, Illinois, June 24, 1908.

10. John Hafen to Thora Hafen, Nashville, Indiana, July 30, 1908.

11. William H. Gerdts, Art across America: Two Centuries of Regional Painting, 3 vols. (New York: Abbeville, 1990), 2:273.

12. John Hafen to Thora Hafen, Nashville, Indiana, November 2, 1908.

13. Norma Hafen Henrie, telephone interview with author, Logan, Utah, March 7, 1996.

14. John Hafen to Thora Hafen, Minneapolis, Minnesota, May 15, 1909.

15. John Hafen to Thora Hafen, Minneapolis, Minnesota, June 9, 1909. This letter is in a typescript compilation of excerpts prepared by the Hafen family. Copy in curatorial files, Museum of Art, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

16. John Hafen to Thora Hafen, June 9, 1909.

17. [John Hafen to President Joseph F. Smith, Nashville, Indiana, August 4, 1909.] This is a rough draft of the letter sent to President Smith.

18. [John Hafen to President Joseph F. Smith.]

19. [John Hafen to President Joseph F. Smith.]

20. The First Presidency of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to John Hafen, Salt Lake City, Utah, October 5, 1909.

21. Armeda to My Dear Friend [John Hafen], Salt Lake City, Utah, December 21, 1909.

22. This original price is supported by Armeda to My Dear Friend, December 21, 1909. Armeda wrote “sold 45 books, gave away 5 my expenses were $6.00. I now with pleasure send you a check of $40.00.”

23. John Hafen to Thora Hafen, Indianapolis, Indiana, November 22, 1909.

24. Tribute given by B. H. Roberts at the funeral of John Hafen, June 9, 1910. John Hafen correspondence file, Special Collections and Manuscripts, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo.

25. In the illustration titles, capitalization and punctuation are Hafen’s.

26. Hafen’s son Virgil was the model for the young man in this painting. Virgil traveled to Minneapolis and then on to Nashville, Indiana, with his father in the spring of 1909.

27. John Hafen to Thora Hafen, Indianapolis, Indiana, December 31, 1909.

28. John Hafen, “Mountains from an Art Standpoint,” Young Woman’s Journal 16 (September 1905): 404.

29. John Hafen to Thora Hafen, Paris, France, October 19, 1890.

30. John Hafen to Thora Hafen, Nashville, Indiana, November 2, 1908; underlining in original.

31. John Hafen to Thora Hafen, Chicago, Illinois, July 23, 1908.

32. Hafen’s daughter Lezetta (called Zetta) was used as the model.

33. Hafen, “Mountains from an Art Standpoint,” 405.

34. John Hafen to an unidentified friend, undated, curatorial files, Museum of Art, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah. This letter is also known as John Hafen’s essay on the mission of art.

35. Hafen, “Mountains from an Art Standpoint,” 403.

36. John Hafen to Thora Hafen, New York, New York, March 12, 1902.

37. John Hafen to Thora Hafen, Nashville, Indiana, July 31, 1909.

38. Quoted in “The Gospel in Art,” Editor’s Table, Improvement Era 13 (December 1909): 177.

39. Alice Merrill Horne, “John Hafen, the Utah Landscapist,” Young Woman’s Journal 21 (February 1910): 88; italics in original.

40. John Hafen to Thora Hafen, Paris, France, December 11, 1890, quoted in LeRoy R. Hafen, The Hafen Families of Utah (Provo, Utah: The Hafen Family Association, 1962), 175–77.

41. John Hafen to President Joseph F. Smith and the Brethren, July 5, 1903, research files, Museum of Church History and Art, Salt Lake City, Utah, quoted in Gibbs, Harvesting the Light, 49.

42. Quoted in “The Gospel in Art,” 177–78.

43. John Hafen, “An Art Student in Paris,” The Contributor 15 (September 1894): 690–91.

- Conversation in Nauvoo about the Corporeality of God

- “O My Father”: The Musical Settings

- Testimony in Art: John Hafen’s Illustrations for “O My Father”

- Changes in the Religious Devotion of Latter-day Saints throughout the Life Cycle

- Celebrating Cultural Identity: Pioneer Day in Nineteenth-Century Mormonism

- Family Land and Records Center in Nauvoo

Articles

- Cast on the Lord

- Leaving Too Soon

- ICU Nursery

- Hymn: Every Kindred, Tongue, and People

- All Tucked In

Poetry

- Three Frontiers: Family, Land, and Society in the American West, 1850–1900

- The Personal Writings of Eliza Roxcy Snow

- Audacious Women: Early British Mormon Immigrants

- Church History in Black and White: George Edward Anderson’s Photographic Mission to Latter-day Saint Historical Sites: 1907 Diary, 1907–8 Photographs

Reviews

- Biographies of Spencer W. Kimball and Boyd K. Packer

- The Legacy of Mormon Furniture: The Mormon Material Culture, Undergirded by Faith, Commitment, and Craftsmanship

- Beyond the River

- Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: Illinois

- Nurturing Faith through the Book of Mormon: The 24th Annual Sperry Symposium

- Kingdom on the Mississippi Revisited: Nauvoo in Mormon History

Book Notices

Purchase this Issue

Share This Article With Someone

Share This Article With Someone