Reverence

Renewing a Forgotten Virtue

Review

-

By

George Bennion,

Paul Woodruff. Reverence: Renewing a Forgotten Virtue.

New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Reverence: Renewing a Forgotten Virtue—the title is straightforward, the subtitle a lament easily understood and therefore not much elaborated. This book by Paul Woodruff (Professor of Humanities at the University of Texas in Austin) is a delight, in part from the beauty and pertinence of the poetry that Woodruff brings in to illuminate his discussion, and from the charm added by his explications. Woodruff is an experienced and widely published translator of Plato, Thucydides, and other classic works, and his prose is a joy as he illustrates the various facets of reverence with brief scenarios and as well as longer stories.

Woodruff begins with a definition of reverence and continues to refine it until the book ends:

Reverence begins in a deep understanding of human limitations; from this grows the capacity to be in awe of whatever we believe lies outside our control—God, truth, justice, nature, even death. The capacity for awe, as it grows, brings with it the capacity for respecting fellow human beings, flaws and all. This in turn fosters the ability to be ashamed when we show moral flaws exceeding the normal human allotment. (3)

This notion of understanding our own human limitations is emphasized throughout the book in many contexts, and is not to be confused with an unwillingness to strive with might and mien nor as a denial that proper motivation can result in amazing accomplishments.

Woodruff presents reverence mainly in social and political settings. In fact, he is at some pains to demonstrate that it is a virtue not necessarily connected to religion. “Reverence has more to do with politics than with religion” (4). “It is a natural mistake to think that reverence belongs to religion. It belongs, rather, to community . . . [and] lies behind civility and all of the graces that make life in society bearable and pleasant” (5). But it stands to reason that religion often promotes reverence. After all, isn’t the function of organized religion to guide us in our daily lives?

Two friends of mine commented separately upon this book, the first saying that he did not think Woodruff religious; the second saying that not many books change many people. As to the second, that sounds more like an indictment of “many readers” than of “many books.” As to the first, if we recall the New Testament definition: “Pure religion and undefiled before God and the Father is this, To visit the fatherless and widows in their affliction” (James 1:27), we are pretty well obliged to see Woodruff as genuinely religious. We may just as easily ask in what way is God religious? Well, in nothing more than in his concern for the helpless and the poor, and in his requirement that we make that our business also.

Though Woodruff’s concern with reverence is pointed at humanity in general, not just the helpless and the poor, it necessarily includes them. In chapter six, “Ancient China: The Way of Power,” we are told that Confucian Li, respect and reverence of every day life, helps keep people from descending into animal behavior on the one hand and on the other from assuming to themselves the prerogatives of heaven. “The ethical consequences are similar; both virtues [dignity and humility] act as restraints on human power, and both work indirectly to protect the weak” (104). “When Zi-you asked about filial piety, the Master said: ‘Nowadays filial piety merely means being able to feed one’s parents. Even dogs and horses are being fed. Without deference, how can you tell the difference?’” (104, quoting Analects 2.7).

Ancient China’s example is very important to Woodruff. He asserts that reverential behavior moves down as well as up social hierarchies and that it is fostered by ritual or ceremony. He notes that filial piety provides a structure for the natural affection of the child for his parents and at the same time gives him practice in behavior beyond the family he will use as an adult. The emperor also, through observance of the ceremonies of courtesy, develops moral sensitivities that enable him to be reverent of his ministers and also of ordinary citizens, in much the same way a father develops respect for his son.

Touching these points, chapter two, “Without Reverence,” contains a vignette titled “Feeding Time.” Family members are scattered to various activities—Dad is with pals, David is at a friend’s house, Mom has brought Sarah home from soccer but has gone to a meeting. Sarah has her algebra on her bed, a bag of chips in easy reach. She has dutifully put food out for the dog, a pet not hungry right now. There will be human food on the table later which may not be eaten by more than one or two people at a time, just when they are hungry. Remind you of Analects 2.7 above? Ceremonies attendant on a family eating together can generate reverence.

Present societal understanding of irreverence is not exactly within the scope of Woodruff’s present concern, but early on he gives it a half-page nod. Americans, and probably everyone else with the latitude to do so, carry on a love affair with some form of irreverence. Referring to the media, Woodruff says,

We hear more praise of irreverence than we do of reverence. . . . That is because we naturally delight in mockery and we love making fun of solemn things. . . . In my view the media are using the word “irreverent” for qualities that are not irreverent at all. A better way to say what they have in mind would be “bold, boisterous, unrefined, unimpressed by pretension”—all good things. (5)

He adds that Nietzsche is the “one great western philosopher who praises reverence” and he “is also the most given to mockery” (5). Semantics may get in our way here. I don’t like ‘mockery’ (to me ugly and destructive) subsumed under ‘reverence,’ but I am fine with ‘unimpressed by pretension.’ The case for irreverence probably should go something like this: Alert, self-respecting people have always been quick to treat people, ideas, and institutions irreverently that to them appear foolish. This irreverence is especially so in people whose lives confront them with hard realities of some sort, and who therefore develop a realism that is impatient, if not disgusted, with triviality, falseness, or smokescreens of whatever variety. Maurice Hilleman, the microbiologist who defeated mumps, measles, and many other diseases, was such a man. It was said of him that he was helpful and pleasant with his students and co-workers, but that “he had zero tolerance for fools.” Most of us love that kind of attitude. If it strikes you that disallowing fools their sway is too much like rudeness, Woodruff would likely say reverence is the capacity to approve or disapprove appropriately. It does not require one to praise or even allow foolishness. Many teachers have delighted in the occasional student whose honesty and whose confidence in his own perceptions have equipped him to detect sham in any of its guises. Such a student acknowledges authority and tradition only when they prove out. This kind of irreverence is often associated with inventiveness, creativity, and exploration. It tends to make society better. Woodruff calls this a part of reverence on the basis that reverence is a virtue that enables people to respond sensitively to bad as well as good situations. The student revolt of the 1960s may have started with something like that—objection to what those students saw as false values in their parents’ generation. But as Woodruff points out, irreverence is seductive. The delight it gives us should be a red flag. Its too easy and too frequent use can be the start of arrogance and hubris (4, 91).

Other plausible scenes presented in chapter two help show the chaos that can flow from groups operating without reverence. The point of one example, titled “God Votes in a City Election,” is clearer when we learn that one party has posted signs all over town, “God voted against Proposition Two.” Woodruff is showing the chasm between misdirected faith and reverence. Another, “Dad Slugs the Umpire,” is also parlayed into the continuing refinement of Woodruff’s definition. A girl in a children’s league is called out on strikes. She is devastated, her furious father commits the crime, and the newscasters with a good story are the big winners. “Learn to control your emotions,” counsels a psychologist (29). But Woodruff uses this story to hone a point: “Virtue, after all, is supposed to be the capacity to have the right emotions from the start. If you have emotions that need to be controlled, you are already in trouble. . . . Even when self-control is called for, it is painful and prone to failure because it runs against our grain. But reverence runs with the grain—or, rather, as you cultivate reverence, you are changing the way your grain runs” (29–30).

One of the longer illustrations occurs in chapter five, “Ancient Greece: The Way of Being Human.” Woodruff mentions two particular concerns of the ancient Greeks that are, naturally, like those of the ancient Chinese: one, the danger of descending into animal behavior, and two, the danger of losing sight of their human limitations. Woodruff reminds us that, in the Iliad, Hector thinks that because he has driven the Greeks back against their ships, he is a greater general than he really is, ignoring the fact that his success is partly due to Achilles’ having withdrawn from the fighting. Blinded thus by false self-esteem, he launches an all-out thrust, strips Achilles’ armor from the careless Patroclus, and vaunts over him as though he had killed Achilles himself. It costs him everything.

Achilles also loses perspective. Grief and anger at the death of Patroclus take his wits away, turn him animal, cause him to refuse suppliants, and stir him to indecent speech. As his death approaches, Hector wants agreement that whoever wins will allow the body of the fallen to be buried. Achilles snarls, “‘Don’t try to cut any deals with me, Hector. / Do lions make peace treaties with men? / Do wolves and lambs agree to get along?’” (87, quoting Iliad 22.261–63). Later, Hector makes a dying request:

“I beg you, Achilles, by your own soul

And by your parents, do not

Allow the dogs to mutilate my body.”

And Achilles, fixing him with a stare,

“Don’t whine to me about my parents,

You dog! I wish my stomach would let me

Cut off your flesh in strips and eat it raw

For what you’ve done to me. There is no one

And no way to keep the dogs off your head.”

(87, quoting Iliad 22.338–48).

In Woodruff’s view, Achilles has utterly failed himself. He argues that even in war we can be reverent, that we are in danger of brutalizing ourselves if we lose sight of our basic humanity, the humanity, in fact, that we share with our enemies and prisoners.

Odysseus seems to have had similar perceptions. After his violent overthrow of the Suitors, he summons his old nurse Euryclea, who has, for the past ten years, endured the violence and threats of the Suitors; she stood as a buffer between them and her mistress, Penelope. When she arrives and surveys the carnage, which until that day had been caused by the Suitors, she sinks to her knees in profound relief and commences an eerie, minor-key cry of triumph, exulting over the vanquished like the tailor-bird Darzee in Kipling’s “Rikki Tikki Tavi.” Odysseus stops her, saying, “Old Woman, it is not meet to exult over the dead” (Odyssey 22.407–16). He sees that, not only in their death but also in their having disgraced their parents, shamed their places of origin, and offended the gods, they have lost enough, and that gloating now would serve no purpose but to debase her and him.

Woodruff’s point brought harshly to mind something I witnessed toward the end of WWII. In northern Luzon, I had walked a few miles up a mountain road to visit a buddy at Division Artillery Headquarters. It happened that while my friend and I were “cooling it” in the shade of some shrubbery, a great cry went up. A starving and unarmed Japanese straggler, cut off from his unit, had risked sneaking into the camp. He was spotted searching the garbage cans for anything he could eat. Many GIs ran howling for their weapons, carbines in that instance, and the pathetic enemy scurried up one of the tall trees nearby. Those trees had no branches for a hundred or hundred fifty feet and then a lot of foliage at the top. In no time, the GI’s were firing at him or at least at the top of the tree. His fall was greeted with gleeful shouts, but when the game ended, something sobered them.

In chapters ten and eleven, “The Reverent Leader” and “The Silent Teacher,” Woodruff endeavors to show how reverence can produce societies large and small that operate under mutual respect, without force or violence. However, he notes that we may never see a purely reverent leader—“one man’s leader is another man’s tyrant” (163)—and warns that it is difficult to practice reverence in an irreverent group. He uses the disastrous affair between Athens and Melos for illustration. Athens was leader of a league of city-states formed to repulse Persia, but over decades had become tyrannical in that role. She sent a force to Melos demanding submission, but the Melians, wanting autonomy, demanded justice. The Athenians put it brutally: Justice can be discussed when both parties are strong, but when only one is strong, it will take all it can and the weak have to accept that. The Melians thought submission would be outright slavery, and resisted. All the Melian men were killed, the women and children enslaved. So we easily see Athens as tyrant, but Woodruff observes that both parties were tyrannical—the Athenians obviously, but the Melian leaders as well because they did not allow their citizens to take part in their deliberations for fear the citizens would accept slavery rather than fight. Leaders, he tells us, must start respect by showing it first, honestly, to their followers—in classrooms or in larger societies. He warns against teachers or leaders acting as though they were infallible (assuming divine attributes), and against anything that would isolate them from their followers. Good leaders listen to their followers, a defense against bad judgment, and they are not offended if followers see flaws in their orders and, on that basis, even disobey.

On the notion that ceremony can support the development of reverence, Woodruff reports that when Oliver North joined a combat unit in Vietnam, his company commander wore a red bandana and allowed his men to call him Organ Grinder. Woodruff’s comment on that: “If you carry guns and dress the part of a bandit, you may find it easier to play the part of a bandit as well” (179). The next commander would not let his lieutenants speak to him until they cut their long hair and otherwise resumed standard appearance. Woodruff ends this section by noting that those who are given weapons for our defense do not hold them in their own service, but in the service of the whole society, thus the greater emphasis on the ceremonies that attempt to guarantee disciplined behavior in those who hold weapons. This principle, he assures us, applies to nonmilitary societies also.

This book is readable—its language plain, its content home fare, its illustrative material charming. But for me the primary values are (1) I was unobtrusively challenged for having forgotten reverence; (2) I was provoked—especially by the ideal of a Chinese emperor learning, through ceremonial behavior, to revere his subjects, like his European counterpart with the ideal of noblesse oblige. Such an ideal does not always take, of course, but what is the alternative? The provocation was this: Is God reverent? Of what could the Great Creator stand in awe? After showing Moses something of his creations, he said, “This is my work and my glory—to bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of man” (Moses 1:39). The size and scope of that divine undertaking argues more than a passing interest. He must see something in us to have made such a huge investment. That something must have to do with our intellect, its potential at least, for he seems willing, against profound regret, to let us slip slowly or plunge precipitately down to hell, but only because he holds that something he sees in us inviolate. Considering the costs to him in labor, compassion, and all the rest, that is an awe-inspiring instance of reverence.

This book is capable of changing some people.

About the author(s)

George Bennion is Professor Emeritus of English, Brigham Young University. He studied Greek literature at Arizona State University in the mid-seventies.

Notes

- The Israelite Background of Moses Typology in the Book of Mormon

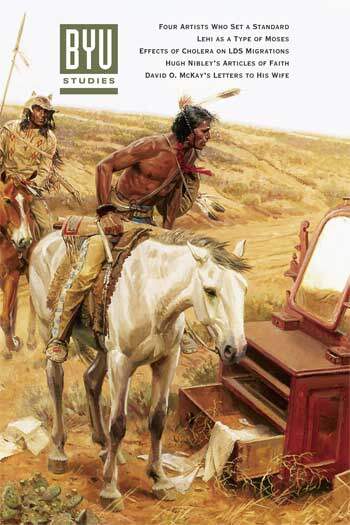

- Setting a Standard in LDS Art: Four Illustrators of the Mid-Twentieth Century

- Hugh Nibley’s Articles of Faith

- Cholera and Its Impact on Nineteenth-Century Mormon Migration

- Memoirs of the Relief Society in Japan, 1951–1991

- Behold I

Articles

- A Superlative Image: An Original Daguerreotype of Brigham Young

- “The Scriptures Is a Fulfilling”: Sally Parker’s Weave

- “Twenty Years Ago Today”: David O. McKay’s Heart Petals Revisited

Documents

- Desert Patriarchy: Mormon and Mennonite Communities in the Chihauhua Valley

- Reverence: Renewing a Forgotten Virtue

Reviews

- Two books on the history of the Church in South America

- Historia de los Santos de los Últimos Días en Paraguay: Relatos de Pioneros

Book Notices

Purchase this Issue

Share This Article With Someone

Share This Article With Someone

Desert Patriarchy

Print ISSN: 2837-0031

Online ISSN: 2837-004X