Religion and Economics in Mormon History

Article

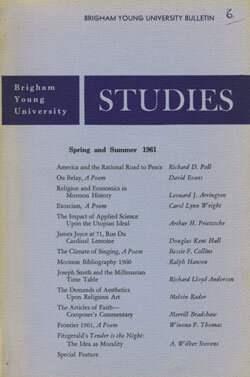

Contents

A number of students of Mormonism, particularly those who are non-Mormon, have found the most startling aspect of Mormonism to be, not the practice of plural marriage, not the belief in a highly personal God, not even the restoration of biblical Christianity or the Book of Mormon or the belief that Joseph Smith received visitations from Heavenly Beings, but the exaltation of economics and economic welfare into an important, if not indispensable, element of religious salvation. Scholars like Weber and Schmoller in Germany, Bousquet in France, Katherine Coman and Frederick Jackson Turner in the United States, have found the essence of Mormonism—or at least the essential contribution of Mormonism—to be in the elevation of economics into the sphere of religion and spirituality.1

Mormonism, according to these scholars, attempted to restore the condition of religion which existed among the early Christians, in which the church was integrated into the daily life of mankind. Religion, the Mormons believed, was not only “a matter of sentiment, good for Sunday contemplation and intended for the sanctuary and the soul,” but also had to do, as one of their leaders said, with “dollars and cents, with trade and barter, with the body and the daily doings of ordinary life.”2 “It has always been a cardinal teaching of the Latter-day Saints,” said Joseph F. Smith, president of the church and nephew of Joseph Smith, “that a religion which has not the power to save people temporally and make them prosperous and happy here on earth, cannot be depended upon to save them spiritually and exalt them in the life to come.”3

Dean D. McBrien, who did a doctoral dissertation in the 1920s under Frederick Jackson Turner, made a special study of the Mormon Doctrine and Covenants and discovered that of the one hundred and twelve revelations announced by Joseph Smith, eighty-eight dealt partly or entirely with matters that were economic in nature.4 Out of 9,614 printed lines in the Prophet’s revelation, 2,618 lines, by actual count, treated “definitely and directly of economic matters.” It was McBrien’s conclusion that “Mormonism, though a religion, is largely, if not primarily, an economic movement, at least insofar as it offers to the world anything that is new.” Reporters, both early and late, observed that the Mormon religion was concerned with the everyday duties and realities of life, and that church leaders were expected to minister not only to the spiritual wants of their followers, but to their social and economic wants as well. An 1837 editor, for example, wrote of the Mormons that there was “much worldly wisdom connected with their religion—a great desire for the perishable riches of this world—holding out the idea that the kingdom of Christ is to be composed of ‘real estate, herds, flocks, silver, gold,’ etc., as well as human beings.”5 And as late as 1904 Ray Stannard Baker wrote: “Mormonism is a broad mode of life, a system of agriculture, an organization for mutual business advancement, rather than a mere church. . . .”6

What is the explanation for this emphasis upon economics in Mormon belief and Mormon history? Why did the Mormons give more attention to temporal matters than most contemporary religions?

Some writers have seen the Mormon emphasis on economics as a heritage from Jacksonian times—a religious rationalization of Brother Jonathan, the Yankee. Mormonism, according to this view, was a kind of coalescence of those two early American philosophies, Puritanism and democracy. This was Ralph Barton Perry’s interpretation. “Mormonism,” he said, “was a sort of Americanism in miniature: in its republicanism, its emphasis on compact in both church and polity, its association of piety with conquest and adventure, its sense of destiny, its resourcefulness and capacity for organization.”7 Count Leo Tolstoi, of Russia, had a similar view. He told Ambassador White that “the Mormon people taught the American religion.”8 He added that he found a certain agrarianism in Mormon philosophy which attracted and delighted him. Above all, he said, “he preferred a religion which professed to have dug its sacred books out of the earth to one which pretended that they were let down from heaven.”

To the devout Latter-day Saint, of course, a more likely reason for the Mormon stress on economics was the word of the Lord to their founding prophet, Joseph Smith. In response to the Prophet’s entreaties, God is said to have revealed the following in 1830: “Verily I say unto you, that all things unto me are spiritual [presumably, even the ‘temporal’], and not at any time have I given unto you a law which was temporal.”9 Accepted by the church in the year of its founding as part of the revealed word of God, this doctrine implied that every aspect of life had to do with spirituality and eternal salvation. As interpreted by Joseph Smith’s successor, Brigham Young, who led the church in the West for thirty years, this revelation meant that “in the mind of God there is no such thing as dividing spiritual from temporal, or temporal from spiritual; for they are one in the Lord.”

We cannot talk about spiritual things without connecting with them temporal things, neither can we talk about temporal things without connecting spiritual things with them. . . . We, as Latter-day Saints, really expect, look for and we will not be satisfied with anything short of being governed and controlled by the words of the Lord in all our acts, both spiritual and temporal. If we do not live for this, we do not live to be one with Christ.10

Orson Hyde, one of Brigham’s apostles, put the matter a little more bluntly. “When we descend to the matter of dollars and cents,” he said in 1853, “it is also spiritual.”11

An excellent example of the practical application of this philosophy was the occasion, in 1856, when a group of Mormon converts who had crossed the Plains with handcarts arrived at the mouth of Emigration Canyon while services were being held in the Old Salt Lake Tabernacle. Word was taken to Brigham Young, sitting on the stand, that these immigrants, cold, tired, and hungry, were about to arrive in the Valley. President Young arose and dismissed the congregation with the following words:

I wish the sisters to go home and prepare to give those who have just arrived a mouthful of something to eat, and to wash them and nurse them up. . . . Were I in the situation of those persons who have just come in, . . . I would give more for a dish of pudding and milk or a baked potato and salt, . . . than I would for all your prayers, though you were to stay here all afternoon and pray. Prayer is good, but when baked potatoes and milk are needed, prayer will not supply their place.12

Whether the Mormon emphasis on economics was an outgrowth of prevailing intellectual trends, or of instructions that were handed down directly from God, however, there can be no doubt that it was strengthened and supported by the social and economic experiences of the early Saints. Extremely important were two early decisions. The first was that they would move their headquarters from New York to Kirtland, Ohio, and Independence, Missouri. This meant that the leaders had to devise ways and means of helping their poor New York members to move westward. Thus, the church had to buy land and develop plans for city growth and development; and it had to initiate financial enterprises and industries to provide employment. Of necessity, the church’s task could not end with the conversion of individual souls. As the germ of the Kingdom of God, it must organize its members, settle them, and assist them in building an advanced society. Ultimately, according to the theology, the church must usher in the literal and earthly Kingdom of God (“Zion”) over which Christ would one day rule.

The second decision was that in which the church assumed responsibility for fighting persecution and for looking after the welfare of its persecuted members. These persecutions drove the group together, made the church a self-conscious nationalistic sect, necessitated frequent removals, and forced the church to organize for the moves and to start planning once more for the purchase of land and for the initiation of industries. Above all, persecution prevented the rise of individualism and removed the surplus wealth which distinguished the wealthy from the poor.

These experiences, and the social, intellectual, and religious origins of Mormonism, led to the development of a set of economic ideals and institutions which became a more or less permanent aspect of Mormon belief and practice, and gave the Mormon community a unique flavor in frontier America. The intimate association of religion with economic activity produced a kind of community planning and community concern which made possible a more just and permanent society than existed elsewhere in the West. Many scholars, in recent years, have pointed out the importance of cooperative activity of this type in achieving and maintaining an advanced social economy. E. C. Banfield, of the University of Chicago, for example, who had previously studied southern Utah, recently made an on-the-spot study of a village (“Montegrano”) in southern Italy. He found the extreme poverty and backwardness of this village to be primarily a result of the “inability of the Montegranesi to act together for their own good or, indeed, for any end transcending the immediate, material interest of the nuclear family.”13 He was struck with the contrast between “Montegrano” and the equally-large community of St. George, Utah, where, with far worse natural resources at their disposal, the Mormon settlers had achieved, through mutual aid and self-government, one of the most highly-organized societies in the West. Others have been similarly impressed with the advanced form of voluntary cooperation in the performance of public tasks in Mormon Country. Partly for this reason, a number of scholars and government officials from such countries as Arabia, Iran, Turkey, Israel, and Lebanon—countries whose geographic conditions are similar—have been studying Utah’s early institutions to see what they can learn that might help them in developing and improving their own countries.

The point is that Mormon economic history, whether in the early years of combating hostile humanity, or in the later years of combating hostile nature, has been more or less an attempt to implement certain specific ideals. And because the Mormons believed that they had been divinely instructed to institute these ideals as a part of the restoration of the Christian Gospel, they have sought to achieve the ideals as a matter of religious salvation.

These historic Mormon economic ideals can be summarized, for convenience, under four headings: (1) Ecclesiastical promotion of economic growth and development, or what the Mormons called “building the Kingdom of God”; (2) ecclesiastical sponsorship of economic independence or group economic self-sufficiency; (3) the attainment of these goals through organized group activity and cooperation; and (4) the search for programs to achieve and maintain economic equality.

Promotion of economic growth. Under an early revelation, the newly-organized church initiated community economic activity by instructing the members to “gather” together in “Zion” to build the Kingdom of God and prepare for the Millennium. A September 1830 revelation stated: “. . . ye are called to bring to pass the gathering of mine elect . . . the decree hath gone forth from the Father that they shall be gathered in unto one place, upon the face of this land . . . .”14

This policy of “accumulating people” as a prerequisite to building the Kingdom was implemented in the 1830s and subsequent decades by the development of a large and highly effective missionary system, an overseas emigration service, and the establishment of a series of Zions or gathering places. Recent studies by Professors William Mulder, Philip Taylor, and Gustive Larson have described the system by which 5,000 European converts were assisted in migrating to Nauvoo, Illinois; the method by which the 25,000 persons in Nauvoo and vicinity were organized in 1846 to make the great trek to Omaha, Nebraska, and later to the Salt Lake Valley; the Perpetual Emigrating Fund Company, which directed the migration of European members to the Salt Lake Valley in the 1850s and 1860s; and the concluding phases of the gathering in the age of the steamship and railroad.15 As the result of these activities and institutions, donations of Utah church members in the form of cattle, grain and other produce were converted into passenger fares, covered wagons, and oxen, and as much as $10,000,000 was expended to assist some 80,000 persons to move to Mormon settlements in the West. This organization, which Katherine Coman called “the best system of regulated immigration in United States history,” continued until disbanded by Congress in 1887.16

The newly-arrived converts and immigrants were first put to work building the Kingdom by means of a church public works system. Centering around Temple Square in Salt Lake City, the Church Department of Public Works undertook to provide employment for the immigrants during their first winter in the Salt Lake Valley, and at the same time add such useful structures to the commonwealth as roads, walls, meetinghouses, railroads, telegraph lines, canals, the Salt Lake Theatre, and the famous Temple and Tabernacle.

After this first winter of labor on church public works the new arrivals were dispatched in organized “companies” and settled in outlying agricultural villages. The property rights and holdings of these villagers were allocated and regulated in order to ensure the highest possible development of resources. The principle which governed here was the principle of stewardship. This was also the result of heavenly instructions in 1830, when the people were told: “Every man shall be made accountable unto me, a steward . . . . And if thou obtainest more than that which would be for thy support, thou shalt give it into my storehouse.”17 In other words, the earth was the Lord’s, and every man must consider his rights to land as “consecrated” for the building of His Kingdom on earth. Conditional upon use, property rights would not be granted or protected if the owner refused to utilize or develop the property. Indeed, the very first pronouncement of Brigham Young in regard to the government of the infant Mormon colony in the Salt Lake Valley included the following stipulation:

No man will be suffered to cut up his lot and sell a part to speculate out of his brethern. Each man must keep his lot whole, for the Lord has given it to us without price . . . . Every man should have his land measured off to him for city and farming purposes, what he could till. He might till as he pleased, but he should be industrious and take care of it.18

This policy seems to have been rather closely adhered to. The speculative withholding of land from use was prohibited, and the purchase or appropriation of town lots for the sake of the increase in value was prevented. An example of ecclesiastical enforcement of this policy is told by Marriner W. Merrill, later a high church official, in his published diary. Upon deciding to venture on his own after a period of hiring himself out as a laborer, Brother Merrill, in 1854, located in the Salt Lake Valley some waterless land which was considered to be outside the margin of irrigation. In his words,

I found on further inquiry that Brother Goudy Hogan claimed the land. This tract of land contained 100 acres. I applied to Brother Hogan to buy his claim as he had plenty of land without it, and as it had cost him nothing I thought I was entitled to a portion of the public domain to build a home upon. Brother Hogan refused to sell or let me have the land or any portion of it, and I felt that he was selfish and did not love his brother as the precepts of the Gospel require. So I applied to the Bishop, John Stoker, but did not get any encouragement from him, he letting me think there was no water for the land and that it was worthless to me. But I did not view things in that light exactly, although I was not at that time acquainted fully with the importance of irrigation to mature crops. So I applied to the Territorial Surveyor, Jesse W. Fox, who was very kind to me and gave me all the information he could about the land, and even took me up to President Young’s office to talk to him about it. President Young did not favor the policy of one man claiming so much land and directed the surveyor, Brother Fox, to make me out a plot of the land for the 100 acres and also to give me a surveyor’s certificate for it. This was done, and on presenting my claim to Brother Hogan he was very angry and said many hard things to me. But he surrendered his claim and I was the lawful claimant of 100 acres of land by the then rules of the country.19

This policy seems to have been rather closely adhered to. forms of property—to money and heavy equipment and other capital goods. It was, for example, against church rules for a man to hoard money or property. Brigham Young said:

When we first came into the Valley, the question was asked me, if men would ever be allowed to come into this Church, and remain in it, and hoard up their property. I say NO. . . . The man who lays up his gold and silver, who caches it away in a bank or in his iron safe, or buries it up in the earth, and comes here, and professes to be a Saint, would tie up the hands of every individual in this kingdom, and make them his servants if he could. It is an unrighteous, unhallowed, unholy, covetous principle; it is of the devil and is from beneath “I would disfellowship a man who had received liberally from the Lord, and refused to put it out to usury.”

“You know very well,” he concluded, “that it is against church doctrine for men to scrape together the wealth of the world and let it waste and do no good.”20

After the settlement of villages and the determination of property rights, the Saints were to proceed with the orderly development of local resources. This was a sacred assignment and was to be regarded as a religious as well as a secular function. One of the Articles of Faith of the church read: “We believe . . . that the earth will be renewed and receive its paradisiacal glory.”21 As explained by a leading apostle in an authoritative work, Latter-day Saints believed that the earth was under a curse and that it was to be regenerated and purified, after which war and social conflict generally would be eliminated and the earth would “yield bounteously to the husbandman. . . . The City of God would then be realized at last.”22

This purification was not to be accomplished by any mechanistic process nor by any instantaneous cleansing by fire and/or water. It was to be performed by God’s chosen; it involved subduing the earth and making it teem with living plants and animals. Man must assist God in this process of regeneration and make the earth a more fitting abode for himself and for the Redeemer of Man. The earth must be turned into a Garden of Eden where God’s people would never again know want and suffering. The Kingdom of God, in other words, was to be realized by a thoroughly pragmatic mastery of the forces of nature. An important early admonition to be industrious, and not idle, was supplementary to this belief.

Making the waste places blossom as the rose, and the earth to yield abundantly of its diverse fruits, therefore, was more than an economic necessity; it was a form of religious worship. As one early leader later wrote, the construction of water ditches was as much a part of the Mormon religion as water baptism. The redemption of man’s home (the earth) was considered to be as important as the redemption of his soul. The earth, as the future abiding place of God’s people, had to be made productive and fruitful and transformed into a virtual Garden of Eden. This would be accomplished, he wrote, “by the blessing and power of God, and . . . by the labors and sacrifices of its inhabitants, under the light of the Gospel and the direction of the authorized servants of God.”23

When the Mormons reached the Great Basin, this concept stimulated tremendous exertion. “The Lord has done his share of the work,” Brigham Young told them; “he has surrounded us with the elements containing wheat, meat, flax, wool, silk, fruit, and everything with which to build up, beautify and glorify the Zion of the last days.” “It is now our business,” he concluded, “to mould these elements to our wants and necessities, according to the knowledge we now have and the wisdom we can obtain from the Heavens through our faithfulness. In this way will the Lord bring again Zion upon the earth, and in no other.”24

The acceptance of the principle of resource development explains the passionate and devoted efforts of the Mormon people to develop the resources of the Great Basin to the full extent of their potentiality. While it was a sacred duty of Latter-day Saints to purify their hearts, it was an equally sacred duty for them to devote labor and talent to the task of “removing the curse from the earth,” and making it yield an abundance of things needed by man. Devices for converting arid wastes into green fields thus assumed an almost sacramental character; they served to promote an important spiritual end.

Economic Independence. The goal of colonization, of the settled village, and of resource development was complete regional economic independence. The Latter-day Saint commonwealth was to be financially and economically self-sufficient. A “law” of the church established this principle in 1830: “. . . let all thy garments be plain, and their beauty the beauty of the work of thine own hands, . . . contract no debts with the world.”25

This revelation appears to have been given much wider application than a literal reading of the original revelation would seem to justify. The Mormon people were asked to manufacture their own iron, produce their own cotton, spin their own silk, and grind their own grain. And they must do this without borrowing from “outsiders.” Self-sufficiency was a practical policy, it was reasoned, because God had blessed each region with all of the resources which were necessary for the use of the people and the development of the region. As a result of the application of this principle, the Great Basin was the only major region of the U.S. whose early development was largely accomplished without outside capital.

The officially-sponsored projects to bring the goal of self-sufficiency closer to realization included the Iron Mission, consisting of about 200 families who devoted strenuous efforts to the task of developing the iron and coal resources near Cedar City; the Sugar Mission, in which several hundred people were united in the 1850s in an effort to establish the sugar beet industry in Utah; the Lead Mission, in which some fifty men were called to work lead mines near Las Vegas, Nevada, to provide bullets and paint for the Kingdom; the Cotton Mission, in which more than a thousand families were sent to southern Utah to raise cotton, olives, grapes, indigo, grain sorghum, and figs; the Silk Mission, which involved the growing of mulberry trees and establishment of a silk industry in every community in the region; and the Flax Mission, Wool Mission, and even, it is somewhat surprising to learn, a Wine Mission.

It is to be emphasized that these were not the isolated and desultory efforts of private individuals experimenting, as Americans have always experimented, with new products; but part of a calculated campaign to achieve self-sufficiency in order to prepare for the Millennium. Many of Utah’s industries received their impetus from this early idealistic motivation for an economically independent Kingdom.

Unity and Co-operation. The quality required to successfully execute the economic program of the church was unity and the accompanying method of organizing for the pursuit of economic goals was co-operation. The seminal revelation enjoining unity was given in January 1831: “I say unto you, be one; and if ye are not one, ye are not mine.”26As one of the most outstanding and easily-recognized traits of the Latter-day Saints, this group spirit was induced partly by the belief that unity was a Christian virtue, and partly by the trying times through which members of the church were to pass in their efforts to establish an independent commonwealth. The symbols of unity were a strong central organization and self-forgetting group solidarity. The participants in the sublime task of building the Kingdom were to submit themselves to the direction of God’s leaders and to display a spirit of willing cooperation. More than a term denoting willingness to work together harmoniously, co-operation was a technique of organization by which migrations were effectuated, forts erected, ditches dug, and mills constructed. Co-operation meant that every man’s labor was subject to call by church authority to work under supervised direction in a cause deemed essential to the prosperity of the Kingdom.

While unity and co-operation characterized the early church, it remained for Brigham Young to develop the technique of unified action and combined endeavor to its well-known perfection. It was his aim that the church come to represent one great patriarchal family:

I will give you a text: Except I am one with my good brethren, do not say that I am a Latter-day Saint. We must be one. Our faith must be concentrated in one great work—the building up of the Kingdom of God on the earth, and our works must aim to the accomplishment of that great purpose.

I have looked upon the community of Latter-day Saints in vision and beheld them organized as one great family of heaven, each person performing his several duties in his line of industry, working for the good of the whole more than for individual aggrandizement; and in this I have beheld the most beautiful order that the mind of man can contemplate, and the grandest results for the upbuilding of the Kingdom of God and the spread of righteousness upon the earth. . . . Why can we not so live in this world?27

Fortified by this conviction, he instituted countless programs to achieve unity and facilitate co-operation. These included co-operative arrangements for migration, colonization, construction, agriculture, mining, manufacturing, merchandising—and, in fact, for every realm of economic activity.

The Mormon passion for unity and solidarity, strengthened and tempered as it was by years of suffering and persecution, at once provided both the means and the motive for regional economic planning by church authorities in the Great Basin. The means was provided by the willingness of church members to submit to the “counsel” of their leaders and to respond to every call, spiritual and temporal. The motive was provided by the principle of oneness itself, which was regarded as of divine origin, and whose attainment required planning and control by those in authority.

Equality. One final aspect of the church’s economic program was that which pertained to justice in distribution. It should be obvious that development principles were the major emphasis of Mormon economic policy. In “working out the temporal salvation of Zion,” to use a contemporary expression, the formulators of church policy centered primary attention on production and the better management of the human and natural resources under their jurisdiction. Nevertheless, early Mormonism, influenced by its own necessities and by the democratic concepts of the Age of Jackson, was distinctly equalitarian in theology and economics, and this had significant influences on church policies and practices in the Great Basin.

The Latter-day Saint doctrine on equality was pronounced within a few months after the founding of the church: “. . . if ye are not equal in earthly things, ye cannot be equal in obtaining heavenly things. . . .”28 There was an earnest and immediate attempt to comply with the spirit of this revelation. In May 1831, when the New York converts to the infant church began to arrive at the newly-established gathering place of Kirtland, Ohio, Joseph Smith instructed that land and other properties be allotted “equal according to their families, according to their circumstances, and their wants and needs. . . . let every man . . . be alike among this people, and receive alike that ye may be one. . . .”29 In a subsequent revelation to the Saints in Ohio the Prophet instructed: “. . . in your temporal things you should be equal, and this not grudgingly, otherwise, the abundance of the manifestations of the Spirit shall be withheld.”30 When the stewardship system was tried in Jackson County, Missouri, similar instructions were given: “And you are to be equal, or in other words, you are to have equal claims on the properties, for the benefit of managing . . . your stewardships, every man according to his wants and his needs, inasmuch as his wants are just.”31

Although the goal of equality seemed to become less important with advances in well-being, the core of the policy was reflected in the system of immigration, the construction of public works, the allotment of land and water, and the many co-operative village stores and industries. In immigration, the more well-to-do were expected to donate of their means to assist in migrating the poorer converts of the church. In the construction of public works, again, those with a surplus were expected to contribute of their surplus; and land and water were parceled out equally to all by means of community drawings.

But the influence of the ideal of equality was still wider; it led to several attempts to completely reorganize society and put economic affairs on the same basis as during the time of the early Christian apostles, of whom it was written in the Acts of the Apostles: “All that believed were together, and had all things common; and sold their possessions and goods and parted them to all men, as every man had need.” Ideal or Utopian-like communities were attempted by the Latter-day Saints in Thompson and Kirtland, Ohio; Independence and Far West, Missouri; and in sixty or seventy communities in the Far West, from Paris, Idaho, on the North, to Bunkerville, Nevada, and Joseph City, Arizona, on the South. In general, these “co-operative communities,” as they were called, were characterized by a high degree of economic equality, and while most of them lasted only a short time, their influence on Utah’s institutions can be seen even today.

What has happened to these economic ideals? To some extent, of course, they still characterize Mormon goals. Through the Church Welfare Plan, Zion’s Securities Corporation, the Presiding Bishop’s Office, and various “church corporations” the church is still carrying out a mammoth program of development. In the Welfare Plan, the attempt is still being made to achieve a workable amount of economic independence by a program of “taking care of our own.” In the Welfare Plan, Labor Missionary Program, and in Mormon enterprises generally, a surprising degree of unity and co-operation is still being maintained. As for methods of financing, partly because of the highly progressive federal income tax, a satisfactory amount of equality is realized.

It would be fair to say, however, that the church would have been able through the years to go much further in achieving these goals if the federal government had not intervened to prevent it. There was, until the 1920s, a more or less consistent effort on the part of Congress and the national administration to force the Mormons to change some of their ideals and practices. To mention only the most important examples, there was, first of all, the dispatching of some 5,000 troops to Utah in 1857–1858 to put down the so-called “Mormon rebellion” and prevent any possibility of an independent Kingdom. There followed, in 1862, the Anti-Bigamy Act, which contained a clause disincorporating the Mormon Church and prohibiting it from owning more than $50,000 worth of property, exclusive of meetinghouses, parsonages, and burial grounds. While this was thought to be unconstitutional (its constitutionality was later upheld), it tended to limit church-sponsored group economic activity. Then there was a series of hostile bills in the late 1860s and 1870s, some of which were enacted by Congress and some of which missed passage by narrow margins.

The most influential of all the “Anti-Mormon” bills was the Edmunds Act, passed in 1882, which, in essence, removed the government of Utah from the hands of the Mormons and placed it in the hands of a commission appointed by the national president. It was quickly followed, in 1887, by the Edmunds-Tucker Act, in which Congress provided for the confiscation of the properties of the Mormon Church. Eventually, church leaders found it necessary to give up the unequal struggle and attempted to bring their ideas and practices more into conformity with the prevailing sentiment of the federal Congress. National leaders and church leaders are said to have entered into a “compact.” We do not know whether such a “compact” was actually made, but at least the agreement and actions which it is said to have involved did take place. In the supposed “compact,” national leaders are said to have promised statehood for Utah provided three things were done: (1) Plural marriage was abandoned; (2) the church political party was dissolved; and (3) the church dissolved its relations with the economy. Plural marriage, of course, was abandoned with the Manifesto of 1890; the Peoples’ party was dissolved in 1891 and the people were divided between Republicans and Democrats; and the church began to take steps to withdraw from many of its economic activities.

However, in one of those strange coincidences of history, the panic of 1891 occurred, ushering in the severe depression of the 1890s. This depression lasted until about 1898. Utah, whose agriculture and mining were marginal, suffered perhaps more severely than any other state in the Union. Unemployment, underemployment, and low farm incomes were ever-present realities. Imbued with the idealism they had learned from Joseph Smith, church leaders decided to use whatever resources were at their command for the expansion and improvement of Utah’s economy. As a result of their concerted efforts, many new and successful industries were initiated. With an investment of about $500,000 the manufacture of sugar was initiated; another $500,000 saw the initiation of the hydroelectric power industry in the West; some $250,000 was expended on the development of a salt industry on the shores of Great Salt Lake. The Saltair recreation resort was constructed, as a means of providing employment; railroads were projected; canals were built; new colonies given a start—in short, everything possible was done to expand the economic base of the Great Basin and surrounding regions.

This was disturbing to national political leaders who, at the turn of the century, were composed of or dominated by industrial leaders—the so-called financial tycoons or “captains of industry.” When Reed Smoot, an apostle of the church, was elected to the United States Senate, therefore, certain persons took advantage of the hearing into his fitness to serve to inquire into the relations between the Mormon Church and business in the intermountain region. Something like a fourth to a third of the testimony in the Smoot trial is concerned with the attempt to show that the Mormon leaders had broken the alleged “compact” and had continued to dominate the economy of the region, to the detriment of private enterprise. The trial embarrassed the church and was, in some respects, vicious, but it was clear that Apostle-Senator Smoot would not be seated and the investigation not concluded unless certain concessions were made by the church. It is during this period, then, that the church sold most of its business interests—and sold them primarily to eastern businessmen. Its interests in the sugar and salt industries, in railroad and hydroelectric power, its coal and iron lands, its telegraph system—its interests in these and other industries were sold to eastern capitalists. For at least a decade, Utah’s economy came to resemble that of other states in the region—Nevada, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho.

Nevertheless, within the past two decades, national sentiment has been more sympathetic to church-sponsored endeavors. In recent years, with the Welfare Plan and other enterprises, the economic ideals of early Mormonism are once more reasserting themselves. Latter-day Saint leaders are confident that they are once more on their way toward the re-establishment of those institutions which are an essential forerunner of the coming of the Son of Man.

About the author(s)

Dr. Arrington is professor of economics at Utah State University.

Some passages in this essay are taken with permission from Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830–1900 (Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press, copyright 1958, by the President and Fellows of Harvard College). Research for this article was done under a grant from the Utah State University Research Council.

Notes

1. Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, trans. Talcott Parsons (London 1930), p. 264, note 25; Albert Edgar Wilson, “Gemeinwirtschaft und Unternehmungsformen im Mormonenstaat,” in Gustav Schmoller’s Jahrbuch für Gesetzgebung, Verwaltung und Volkswirthschaft im Deutchen Reich (39 vols; Leipzig, 1877–1915), 31 (1901), 1003–56; G. H. Bosquet, “Une Théocratie Economique: L’Eglise Mormone,” Revue d’ économie politique, 50 (Part 1, 1936), 106–145; Katherine Coman, Economic Beginnings of the Far West (2 vols.; New York, 1912), 2:167–206; and the following by a student of Frederick Jackson Turner: Dean D. McBrien, “The Influence of the Frontier on Joseph Smith” (Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, George Washington University, 1929).

2. “Religion and Business,” Deseret News (Salt Lake City), October 29, 1877.

3. Joseph F. Smith, “The Truth about Mormonism,” Out West, 23 (1905), 242.

4. Dean D. McBrien, “The Economic Content of Early Mormon Doctrine,” Southwestern Political and Social Science Quarterly, 6 (1925), 180. McBrien used the Lamoni, Iowa, 1911 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants published by the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Independence, Missouri. This resembles Salt Lake City editions but it is not identical with them. Brigham Young, incidentally, substantiates this finding. He stated: “The first revelations given to Joseph were of a temporal character, pertaining to a literal kingdom on the earth. Most of the revelations . . . pertained to what the few around him should do in this or that case . . . that they might begin to organize a literal, temporal organization on the earth.” Sermon of January 17, 1858, Journal of Discourses (26 vols., Liverpool, 1841–1886), 6:171.

5. S. A. Davis in Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate, 3 (April 1837), 489–491.

6. Ray Stannard Baker, “The Vitality of Mormonism: A Study of an Irrigated Valley in Utah and Idaho,” The Century Magazine, 68 (1904), 174.

7. Ralph Barton Perry, Characteristically American (New York, 1949), 97–98.

8. Autobiography of Andrew Dickson White (2 vols.; New York, 1907), 2:87.

9. The Evening and The Morning Star, 1 (September 1832), [2].

10. Sermon of June 22, 1864, Journal of Discourses, 10:329.

11. Sermon of September 24, 1853, ibid., 2:118.

12. Sermon of November 30, 1856, Deseret News, December 10, 1856.

13. Edward C. Banfield, The Moral Basis of a Backward Society (Glencoe, Ill., 1958), 7–19, 37.

14. The Evening and The Morning Star, loc. cit.

15. William Mulder, Homeward to Zion: The Mormon Migration from Scandinavia (Minneapolis, 1957); Philip A. M. Taylor, “Mormon Emigration from Great Britain to the United States 1840–70” (Unpublished Ph.D., dissertation, University of Cambridge, 1950); Gustive O. Larson, Prelude to the Kingdom: Mormon Desert Conquest (Francestown, N. H., 1947).

16. Coman, op. cit, 2:184.

17. Doctrine and Covenants (Kirtland, Ohio, 1835), 42:31–35.

18. William Clayton’s Journal (Salt Lake City, 1921), p. 326; Brigham H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: Century I (6 vols., Salt Lake City, 1930), 3:269.

19. Utah Pioneer and Apostle, Marriner Wood Merrill and His Family, ed. Melvin Clarence Merrill (Salt Lake City, 1937), p. 36.

20. Sermon of June 5, 1853, Journal of Discourses, 1:252–255. Italics in original.

21. Joseph Smith, History of the Church . . . (2nd ed.; 6 vols.; Salt Lake City, 1946), 4:541.

22. James E. Talmage, A Study of the Articles of Faith (19th ed.; Salt Lake City, 1940), p. 377.

23. “A Practical Religion,” Deseret Weekly (Salt Lake City), October 16, 1897), p. 553.

24. Sermon of February 23, 1862, Journal of Discourses, 9:283–284.

25. The Evening and The Morning Star, 1 (July 1832), [1].

26. Ibid., 1:[5].

27. Sermons of October 7, 1859; January 12, 1868, Journal of Discourses, 7:280, and 12:153.

28. Doctrine and Covenants, 75:1.

29. Ibid., 23:1.

30. Ibid., 26:3.

31. Ibid., 86:4.

- America and the Rational Road to Peace

- Religion and Economics in Mormon History

- The Impact of Applied Science upon the Utopian Ideal

- James Joyce at 71, Rue Du Cardinal Lemoine

- Joseph Smith and the Millenarian Time Table

- The Demands of Aesthetics upon Religious Art

- The Articles of Faith—Composer’s Commentary

- Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night: The Idea as Morality

Articles

- Special Feature: Letter to Thomas E. Cheney

Notes and Comments

- Mormon Bibliography 1960

Bibliographies

Purchase this Issue

Share This Article With Someone

Share This Article With Someone