Outward Bound

A Painting of Religious Faith

Article

-

By

Richard G. Oman,

Contents

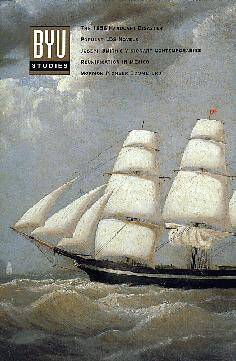

Outward Bound, January 17, 1853 Golconda was painted in 1876, in the high desert valley of the Great Salt Lake, over seven hundred miles from the nearest ocean. It was undoubtedly a commissioned work of art, appointed not by the owner or captain of the ship, as were most marine paintings of the time, but probably by someone who traveled in “steerage,” the most humble accommodations on the ship. These elements alone make this painting unique.

At first glance, Outward Bound appears to be similar to many marine paintings from the nineteenth century.1 While the image and style of this painting are not distinctive, its context and meaning are noteworthy—significant now, as well as at the time of its creation over a century ago. Ultimately, it is a painting about religious faith, documenting the obedience of LDS converts in Europe to the call of a prophet in far-off Utah, as well as the generosity of the Saints in Utah to European Saints whom they had never met.

The Golconda was a ship chartered by the Perpetual Emigrating Fund2 to bring new converts from Liverpool to America. The funding for the charter was heavily subsidized by contributions from the Saints in Utah. Most of the passengers on this ship left Europe in response to the call for the Saints to gather in Zion, and most would never see their native lands again.

The Ship

Outward Bound is a rare painting of a Mormon emigrant ship painted by a Latter-day Saint artist.3 The work is a highly accurate rendition of this British merchant ship that carried Latter-day Saints on two different voyages from Liverpool to the New World. The Golconda was launched in St. Johns, New Brunswick, Canada, in 1852. A large Atlantic merchant ship for its time,4 the ship was registered in Liverpool and sailed under the flag of the British merchant marine.5

Though Ottinger probably never saw this ship,6 he is amazingly exact in depicting a British packet ship built in the late 1840s or the early 1850s. The artist’s care in accurately depicting the ship is demonstrated in the following details: The figurehead is present but truncated. Before the late 1840s, the figurehead would have been full sized, and after the mid-1850s, it would have been eliminated altogether. The “gun stripe” along the side of the ship is shown, but without painted “gunports.” Prior to this period, black gunports would have been painted onto the white gun stripe. Afterward, even the stripe itself would have been eliminated.7 The ship’s deckhouse is green—the era’s most popular color for deckhouses—and the Golconda’s flag accurately flies the insignia of the British merchant marine. The top mainsail (the second sail up from the bottom sail on the mast) of the Golconda is a very large single sail, and the ship’s total number of sails per mast is four. Later, shipbuilders increased this number to six by splitting the large top mainsail into two smaller sails for easier management and by adding another smaller sail to the top of the mast.8

The Captain

The captain of the Golconda was George Kerr, who was respected and beloved by the Mormon emigrants on his ship. The Millennial Star noted that Captain Kerr’s conduct “gave great satisfaction to all the company [and before parting] a vote of thanks, with three cheers, was tendered him.”9 While favorable comments were not rare for a captain of a Mormon emigrant ship,10 most captains did not receive such an accolade. Kerr was the captain on both voyages that carried Latter-day Saint emigrants in 1853 and again in 1854.11

The 1853 Voyage

The painting shows the Golconda sailing out of Liverpool on January 23, 1853,12 with 321 Latter-day Saint passengers aboard.13 In the mid-nineteenth century, Liverpool was the center of world maritime commerce. A bustling port city of over two hundred thousand people, it had the finest dock facilities in the world. Upwards of twenty thousand ships sailed in and out of the Liverpool harbor yearly.14

The entrance to the Liverpool harbor is clearly, but economically, stated in the painting. A buoy, prominently painted in the lower right corner, clearly indicates the shipping channel. The scene is full of sailing ships, communicating the busy nautical traffic of the harbor. To the right stands the harbor entrance lighthouse—a prominent landmark. In the background, one can dimly see the Liverpool docks fading into the haze as the Golconda sails away from the English shores. The mainsail on the mainmast is still in the process of being set. Ships were usually towed out to the harbor entrance by steam tugs. As the lines linking tugboat and ship were cast off, the ship’s sails were set. The Golconda is depicted in the final phase of setting its sails, clearly indicating the beginning of the voyage and reinforcing the title, Outward Bound, given the painting by the artist.

On the 1853 voyage, the Golconda’s destination was New Orleans. The voyage was apparently, for the most part, a positive experience, but not without incident: “During the crossing a brief storm wrecked the vessel’s three top masts. Two emigrants died, two couples were married, four babies were born, and a Swedish sailor was baptized.”15 Upon arrival in New Orleans, the company of Saints, led by Jacob Gates,16 transferred to a 682-ton wooden steam packet, the Illinois, probably commanded by Captain David T. Smithers. The Illinois transported the Saints to St. Louis and then on to Keokuk, Iowa.17

The Patron of the Painting

I believe this painting was probably commissioned by a person who, as an LDS emigrant, had sailed on the Golconda and wanted to commemorate the experience. Outward Bound was created in 1876, almost a quarter of a century after the ship had sailed from Liverpool. Paintings commemorating historical events are frequently done in retrospect, after a historical perspective has been achieved. For example, just two years after the Golconda was painted, C. C. A. Christensen painted his famous series, Mormon Panorama, to memorialize pre-Utah Mormon history.

Extreme limitation of financial resources in the early days of pioneer Utah was another probable reason for the delay in commissioning the painting. Emigrants often arrived in debt to the Perpetual Emigrating Fund. With time, individual financial resources increased. Life became less of a hard scramble, leaving time for people to reflect on the meaningful events of their lives. Sailing across the Atlantic on the Golconda was undoubtedly a “crossing of the Rubicon” for the LDS emigrants on board. A painting was an excellent way to commemorate this life-changing event.

The Artist

George M. Ottinger was born in Springfield Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, on February 8, 1833. He was the third child of William and Elizabeth Ottinger.18 As a youth he traveled to New York City to live with his uncle, a clergyman, and attend school, where the study of history became his favorite subject.

In New York, Ottinger first became entranced with ships and the sea.19 At the age of seventeen, he ran away aboard a whaling ship, the Maria of Nantucket.20 He eventually sailed on other ships until he finally arrived again in New York, having traveled the world, visiting San Francisco, Mexico, Panama, the Galapagos Islands, Peru, Chile, Brazil, South Africa, and China.21 While sailing around the world, he made small sketches. The LDS Museum of Church History and Art owns several of Ottinger’s paintings that document his adventures as a sailor, including a view of Mt. Fuji.22 Ottinger received some additional art training in Philadelphia after returning from sea,23 but he worked mostly in industrial occupations, such as painting carriages and hand coloring photographs.

Ottinger was baptized a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on June 7, 1858.24 In 1861 he set off from Philadelphia with one hundred other Latter-day Saints to cross the plains to Utah, arriving in Salt Lake City on September 12.25 While en route to Utah, Ottinger completed at least three paintings of scenes and events along the way.26 In Salt Lake City, he found work painting scenery in the Salt Lake Theater and eventually went into business with C. R. Savage, a successful photographer and businessman in the arts. The art market in Utah was not very strong, so Ottinger tried a variety of different occupations in order to survive financially. He was on the faculty of the Deseret Academy of Art, where he was elected president. He became an officer in the Nauvoo Legion, the Utah Territorial Militia.27 Eventually, Ottinger became the Salt Lake City fire chief. Ottinger Hall, the Firemen’s Association building named in his honor, stands today at the mouth of City Creek Canyon in Salt Lake City.

Still, it is as an artist that George M. Ottinger is most frequently remembered. During his lifetime, he was perhaps Salt Lake City’s best known painter. His association with C. R. Savage was an asset. Savage’s shop on Main Street in Salt Lake City was centrally located, and his social and professional connections helped bring Ottinger commissions. Aside from his association with Savage, Ottinger himself had a fairly high profile in the community and was known to do commemorative paintings on commission. For example, the Museum of Church History and Art owns a painting of the Mormon Battalion done over thirty years after the time it depicts. The Museum also has an Ottinger painting of the town of Putney, England, that was commissioned by the Squires family, who emigrated from Putney to Salt Lake City.28 Ottinger’s experience as a sailor and his intimate working knowledge of ships made him the perfect choice for a commission to paint the Golconda.

The Significance of Outward Bound

in the History of Mormon Art

Latter-day Saints have recently celebrated the sesquicentennial of the coming of the Mormon pioneers to Utah. Many of the Utah pioneers began their journey aboard a Church-chartered ship sailing out of Liverpool. As the Church becomes increasingly international in membership, it is well to remember that one of the most “American” events in our history—the pioneers coming to Utah—had a significant international component. The ships loaded with LDS converts, the Mormon wagon trains, and the nineteenth-century LDS settlements in the American West were heavily populated with members of the Church from many different countries.

Outward Bound celebrates the broad international aspect of LDS history that began early and continues in our time. The painting also represents acts of faith and consecration. But, perhaps most significantly, as members of the Church from all parts of the world poured into Zion, it represents the bond of fellowship felt by Latter-day Saints, who truly believed that “ye are no more strangers and foreigners, but fellow citizens with the saints, and of the household of God” (Eph. 2:19).

About the author(s)

Richard G. Oman is Senior Curator of the Museum of Church History and Art.

Notes

1. Basil Lubbock, The Western Ocean Packets (Boston: Charles E. Lauriat, 1925; reprint, Glasgow: Brown, Son and Ferguson, 1977).

2. The Perpetual Emigrating Fund was a Church corporation set up to assist the emigration of the poor to Zion. The theory behind it was that Saints in Utah would donate to the fund to assist emigrants in paying for the cost of passage. Once they had arrived in Zion and became established, the emigrants would pay back the cost of their passage. These repaid funds would then go to help others gather to Zion.

3. The other known painting by an LDS artist of a Mormon emigrant ship was painted by pioneer artist C. C. A. Christensen. Richard L. Jensen and Richard G. Oman, C. C. A. Christensen, 1831–1912: Mormon Immigrant Artist (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1984), 40. This tiny painting of the Westmoreland was painted by the artist in 1867, ten years after Christensen left his native Denmark and sailed across the Atlantic on that ship.

4. The tonnage of the Golconda has been variously listed as 1,170, 1,087, 1,044, and 1,224 tons. Sonne, Ships, Saints, and Mariners, 89–90.

5. Conway B. Sonne, Ships, Saints, and Mariners: A Maritime Encyclopedia of Mormon Migration, 1830–1890 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1987), 89–90.

6. The Golconda is not listed in Lloyd’s Register after 1868. Sonne, Ships, Saints, and Mariners, 90. Ottinger did not create the painting until 1876.

7. For centuries mock gunports had been painted on merchant ships to disguise them as men-of-war. These gunports helped foil pirates and privateers that preyed on helpless merchant ships that sometimes carried rich cargoes. After the defeat of Napoleon and the end of the War of 1812, the British navy enforced the Pax Britannica on the high seas, making pirates and privateers mostly a thing of the past, but the old style of painting mock gunports continued for a few decades. The Golconda was painted with a transitional design signaling the end of an old tradition.

8. James Raines, conversation with author, September 29, 1997, Salt Lake City. A nautical historian, Raines is a model ship builder and editor of Ships in Scale, a ship-modeling publication. Raines is also a member of the staff at the Museum of Church History and Art, where he spent several years building the model of the Enoch Train, a Mormon emigrant ship. The model is now on permanent exhibition at the Museum.

9. Editorial, Millennial Star 15 (May 21, 1853): 330.

10. For another example, see Richard J. Dunn, “Dickens and the Mormons,” BYU Studies 8, no. 3 (1968): 334.

11. Sonne, Ships, Saints, and Mariners, 89.

12. Sonne, Ships, Saints, and Mariners, 89. There is a discrepancy here with the January 17, 1853, date on the back of the painting. This could be explained as a lapse in the patron’s memory after almost a quarter of a century, or perhaps it could also be the result of a false start. It was not uncommon for a ship to set off to sea only to have to be towed back into harbor for another try in a few days. Usually these delays were caused by too much wind or no wind at all.

13. Sonne, Ships, Saints, and Mariners, 89.

14. Conway B. Sonne, Saints on the Seas: A Maritime History of Mormon Migration, 1830–1890, University of Utah Publications in the American West, vol. 17 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1983), 33–34.

15. Sonne, Ships, Saints, and Mariners, 89.

16. Sonne, Ships, Saints, and Mariners, 89.

17. Sonne, Saints on the Seas, 105.

18. “Journal of George Martin Ottinger,” typescript, 2, in possession of the author. The original manuscript is in Special Collections, Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

19. “Journal of George Martin Ottinger,” 9–10.

20. “Journal of George Martin Ottinger,” 25.

21. “Journal of George Martin Ottinger,” 28–29, 32, 35, 43, 48–50, 53.

22. Ottinger painted these scenes later in life, after he had emigrated to Utah. Acquisition Records, Museum of Church History and Art, Salt Lake City.

23. “Journal of George Martin Ottinger,” 60.

24. “Journal of George Martin Ottinger,” 60.

25. “Journal of George Martin Ottinger,” 71.

26. Very few paintings exist that were done by pioneer artists while on the Mormon Trail. The Museum of Church History and Art has three paintings that George M. Ottinger completed during his trek to Utah: Burial of John Morse at Wolf Creek; Chimney Rock, August 3, 1861; and Mormon Emigration Train at Green River. Acquisition Records, Museum of Church History and Art, Salt Lake City.

27. “Journal of George Martin Ottinger,” 72–74.

28. Acquisition Records, Museum of Church History and Art, Salt Lake City.

- Weather, Disaster, and Responsibility: An Essay on the Willie and Martin Handcart Story

- Outward Bound: A Painting of Religious Faith

- The Mormon Pioneer Odometers

- A Shepherd to Mexico’s Saints: Arwell L. Pierce and the Third Convention

- Popular and Literary Mormon Novels: Can Weyland and Whipple Dance Together in the House of Fiction?

- The Visionary World of Joseph Smith

Articles

- Having Authority: The Origins and Development of Priesthood during the Ministry of Joseph Smith

- Power from On High: The Development of Mormon Priesthood

- Worth Their Salt: Notable but Often Unnoted Women of Utah

Reviews

- Clothed with Charity: Talks from the 1996 Women’s Conference

- The Balm of Gilead: Women’s Stories of Finding Peace

- Women of the Mormon Battalion

- A Comprehensive Annotated Book of Mormon Bibliography

- Religions of the World: A Latter-day Saint View

Book Notices

Purchase this Issue

Share This Article With Someone

Share This Article With Someone

Weather, Disaster, and Responsibility

Print ISSN: 2837-0031

Online ISSN: 2837-004X