The Five Books of Moses

A Translation with Commentary

Review

-

By

Roger G. Baker,

Robert Alter. The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary.

New York: W. W. Norton, 2004.

There are Bibles aplenty in our world, hundreds if Amazon.com is any guide. In late 2009, Amazon listed over one thousand books on its Bible hit list that have not even been released yet. Over one thousand new books of the roughly 450,000 listed Bible hits portend heavy reading this year for those who try to keep up with things biblical.

A beneficial search in this swim through the Amazon of books is for new Bible translations, which now seem plentiful, although there were very few in the years after King James. An almost three-century gap separates the King James Version (KJV) in 1611 from the next major English translations, the English Revised Version (ERV) in 1881–85 and the American Standard Version (ASV) in 1901. And even though new translations were more frequent in the 1900s, it was not until 1988 that another version, the NIV (New International Version, first published in 1973), outsold the Bible of the Reformation and Restoration that Latter-day Saints still use.1

The question for Latter-day Saint readers is whether or not any of the new translations are important enough to supplement the Authorized Version, or King James Version, which is most commonly used in the Church. In regard to other translations, the Latter-day Saints may sometimes harbor the same mindset we read about in 2 Nephi 29:3: “A Bible! A Bible! We have got a Bible, and there cannot be any more Bible.” Of course, it is unlikely that another translation will match the King James Version in poetic power, but the Saints can learn and benefit from new translations used alongside the familiar Bible.

A reverent familiarity with the King James Version quickened the spirit of Joseph Smith as he petitioned for wisdom during the translation of the Book of Mormon. But it is fair to ask if any Bible translations since the masterpiece of 1611 are valuable to the modern Saints, who live with the caveat “as far as it is translated correctly” (Articles of Faith 1:8). For example, the Saints might want to look at the NRSV (New Revised Standard Version) of 1989 because it “corrects” prior translations with footnotes to the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The latest serious translation of the Bible that may be inviting to Latter-day Saint readers is The Five Books of Moses, translated by Robert Alter, a well-established Berkeley professor of Hebrew and comparative literature. Alter has taken biblical studies in a literary direction over the past few decades with such works as The Art of Biblical Narrative (1983) and The Art of Biblical Poetry (1987). Alter invites us to enjoy the pure pleasures of literature as we read the Bible. Similarly, Alter first justifies his newest work with a literary argument:

Broadly speaking, one may say that in the case of modern versions, the problem is a shaky sense of English and in the case of the King James Version, a shaky sense of Hebrew. The present translation is an experiment in re-presenting the Bible—and, above all, biblical narrative prose—in a language that conveys with some precision the semantic nuances and the lively orchestration of literary effects of the Hebrew and at the same time has stylistic and rhythmic integrity as literary English. (xvi)

Alter accomplishes this objective, and the literary reader will enjoy the style. He is not only successful with his translation, but he also offers footnotes that give insights into his translation decisions. For example, KJV readers come to “firmament” in Genesis and may wonder about its definition, even after noting that the footnote suggests “expanse.” Although Alter’s word choice, “vault,” may lack the poetic ring of the familiar KJV “firmament,” the reader can turn to the footnote and see exactly why Alter chose the term.

Alter also helps the reader with the familiar terms “man Adam” and “Adam,” and in this translation the “help meet” Eve is a “sustainer.” The list of specific footnoted word helps could go on and on. The word in Genesis translated by the King James translators as “know” can be a real problem. The verb yada, translated as “know,” has three meanings in the early Genesis chapters: “to know,” “to understand,” and “to have carnal relations with.”2 In the various instances yada is translated, Alter stays close to the Hebrew. He does make a small change with a comma, rendering the phrase “the tree of knowledge, good and evil.” But the humans “know good and evil” and Adam “knew” Eve. Despite the word helps, it is quickly apparent that Alter is translating the Bible, not explaining it.

Alter’s overall translation is successful because he treats each of the five books of Moses as a coherent book. The academic world has been arguing for two centuries about the four writers whose narrative threads intertwine in Genesis. This documentary hypothesis has fractionalized the scenes of the Bible’s founding narrative. It is interesting that readers do not obsess with explaining every contradiction in an epic novel, but they do when reading Genesis. In such explaining, we find what Alter calls “the unacknowledged heresy underlying most modern English versions of the Bible” (xiv). Modern translators, whether secular or sacred, try with their translations to explain the Bible. A secular, academic translator may try to explain the seven pairs of clean animals in Genesis 7 and the single-paired animals in the flood story in Genesis 6 as a merger of two documents or manuscripts. The sacred, religious translator may downplay any discrepancies and unify the text with doctrinal explanations—the law of animal sacrifice would make it necessary to bring seven pairs because, obviously, sacrificing one member of a sole mating pair would eliminate the species.

It should not be a surprise that the Bible translation heresy is often taken to excess. Fellow “heretics” have spent reams of papyrus, parchment, and paper on small details such as the 153 fish caught in John chapter 21, to the point that now the multifarious explanations on the mysteries of the number 153 have their own Wikipedia entry.3 How refreshing to read Alter’s translation, which does not try to explain the Bible.

Alter’s objective, to avoid the translation heresy of explanation, succeeds for the literary reader. Alter uses English that is loyal to the Hebrew text and captures the nuances of poetic device, both in Hebrew and in English. His translations let the poetry stand. They remain in the spirit of Archibald MacLeish’s well-known couplet: “A poem should not mean / But be.” And because Alter is a faithful poet, we discover that the first poem in the Bible comes early on in Genesis 1. The announcement of Eve’s creation is a poem recited by Adam:

This one at last, bone of my bones

and flesh of my flesh,

This one shall be called Woman,

For from man was this one taken. (22)

The poetry continues; the curse imposed on the first parents is a poem, and God confronts Cain with a poem. The deluge sent by God begins in a poetic rush:

All the wellsprings of the great deep burst

And the casements of the heavens were opened. (44)

Along with the poignant poetry are crisp narratives, even some that make us smile at the last punch line, as when Sarah doubts the possibility of pregnancy in her old age:

And Sarah was listening at the tent flap, which was behind him. And Abraham and Sarah were old, advanced in years, Sarah no longer had her woman’s flow. And Sarah laughed inwardly, saying, “After being shriveled, shall I have pleasure, and my husband is old?” And the LORD said to Abraham, “Why is it that Sarah laughed, saying, ‘Shall I really give birth, old as I am?’ Is anything beyond the LORD? In due time I will return to you, at this very season, and Sarah shall have a son.” And Sarah dissembled, saying, “I did not laugh,” for she was afraid. And He said, “Yes, you did laugh.” (87)

Bible translations of this passage do not get better than this, yet the Authorized Version is not about to be replaced. There are some superior KJV passages that live in the spiritual DNA of Bible readers. When the King James translators had Abraham answer Isaac’s question about the lack of an offering with “God will provide himself an offering,” they opened a metaphorical understanding of the Atonement not present in Alter’s “God will see to the sheep for the offering, my son.”

Though memorable KJV phrases will never be replaced, Alter’s The Five Books of Moses deserves a place more prominent than on a library shelf of Bible translations and commentaries; it should be on the bed stand to be read and enjoyed.

About the author(s)

Roger G. Baker is Professor of English, emeritus, at Brigham Young University. He is the reviewer of “Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism,” BYU Studies 47, no. 2 (2008): 148–51, and author of The Bible as Literature: Out of the Best Book (Ephraim, Utah: Snow College, 1995).

Notes

1. Jack P. Lewis, “King James Version,” in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. David Noel Freedman, 6 vols. (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 6:833.

2. Gerald Hammond, “English Translations of the Bible,” in The Literary Guide to the Bible, ed. Robert Alter and Frank Kermode (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1987), 652; see also 647–66.

3. St. Jerome, the translator of the Vulgate, wrote that the very specific number, 153, was the number of species of fish. The symbolic implication is that every kind of fish (or person) is caught in the gospel net.

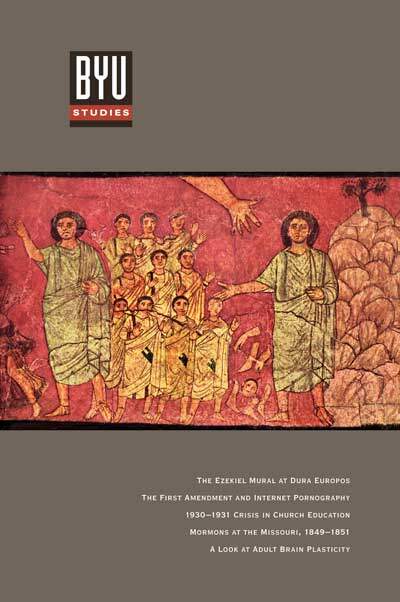

- The Ezekiel Mural at Dura Europos: A Witness of Ancient Jewish Mysteries?

- The Misunderstood First Amendment and Our Lives Online

- Joseph F. Merrill and the 1930–1931 LDS Church Education Crisis

- The Frontier Guardian: Exploring the Latter-day Saint Experience at the Missouri, 1849–1851

Articles

- Sorting, In Evening Light

Poetry

- Twisted Thoughts and Elastic Molecules: Recent Developments in Neuroplasticity

- Religion, Politics, and Sugar: The Mormon Church, the Federal Government, and the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company, 1907–1921

- The Tree House

- The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary

- One Good Man

- It Starts with a Song: Celebrating Twenty-Five Years of Songwriting at BYU

Reviews

- A Different God?: Mitt Romney, the Religious Right, and the Mormon Question

- Proclamation to the People: Nineteenth-Century Mormonism and the Pacific Basin Frontier

- In God’s Image and Likeness: Ancient and Modern Perspectives on the Book of Moses

- Understanding Same-Sex Attraction: Where to Turn and How to Help

- What’s the Harm?: Does Legalizing Same-Sex Marriage Really Harm Individuals, Families, or Society?

Book Notices

Purchase this Issue

Share This Article With Someone

Share This Article With Someone